This fact sheet is also available in Afaan Oromo.

- In 2005, Ethiopia expanded its abortion law to allow abortion in cases of rape, incest or fetal impairment. In addition, a woman can legally terminate a pregnancy if her life or physical health is in danger, if she has physical or mental disabilities, or if she is younger than 18 years old.

- Prior to this expansion, the law had only allowed the procedure to save the life of a woman or to protect her physical health.

- Ethiopia is one of only a few countries that have explicitly reduced barriers to safe and legal abortion for adolescent women.

- In the last decade, the government has published national standards and guidelines on safe abortion that permit the use of medications (misoprostol with or without mifepristone) to terminate pregnancies, in accordance with World Health Organization clinical recommendations on safe abortion.1

- Under the expanded abortion law, abortions performed in health facilities increased from 27% of all abortions in 2008 to 53% in 2014.

Abortion incidence among adolescents

- Evidence on the incidence of induced abortion sheds light on levels of unmet need for family planning and unintended pregnancy among adolescents.

- According to data from 2014, adolescents had the lowest abortion rate among all women younger than age 35 (20 per 1,000 women aged 15–19, compared with 28 per 1,000 women aged 15–49). However, adolescents had the highest abortion rate among sexually active women (81 per 1,000 women).

- There were an estimated 96,000 induced abortions among adolescents in Ethiopia in 2014. This corresponds to 61,000 legal abortions and 35,000 clandestine abortions (those performed outside a health facility).

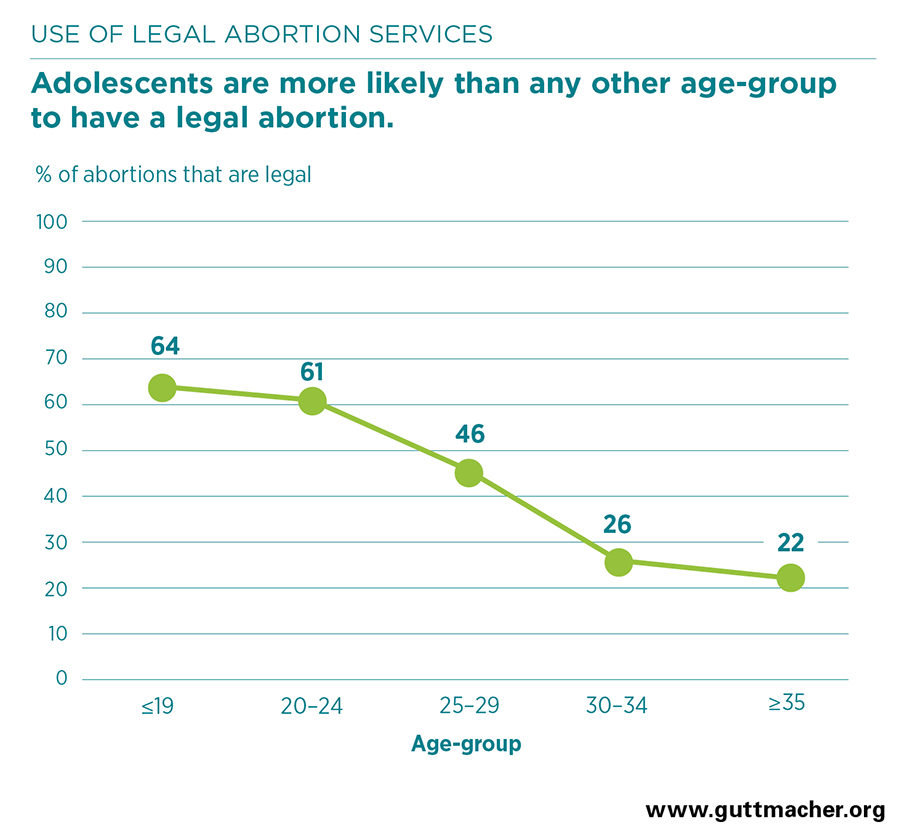

- Women aged 15–19 were more likely than older women to obtain legal abortion services in Ethiopia. Compared with other age-groups, adolescents had the highest proportion (64%) of legal procedures performed in a health facility.

- Compared with that for adolescents, the proportion of abortions that were legal was considerably lower for women aged 25–29 (46%) and for those aged 35 and older (22%).

Adolescents seeking abortion and postabortion care

- In 2014, adolescents seeking postabortion care for complications that likely resulted from a clandestine abortion were more likely than adolescents who had legal abortions to be married (50% versus 18%) and to have had no education (14% versus 5%).

- One in four adolescents seeking postabortion care for complications likely resulting from a clandestine abortion were in the second trimester of their pregnancy, compared with one in 10 adolescents who had legal abortions. Obtaining an abortion at later gestations in clandestine and potentially unsafe circumstances, or delaying postabortion care, may increase the severity of complications.

- The vast majority of adolescents seeking legal abortion or postabortion care were not using a family planning method at the time of their pregnancy (82% and 74%, respectively) and had experienced at least one previous pregnancy (93% for both groups).

Impact of unintended pregnancy

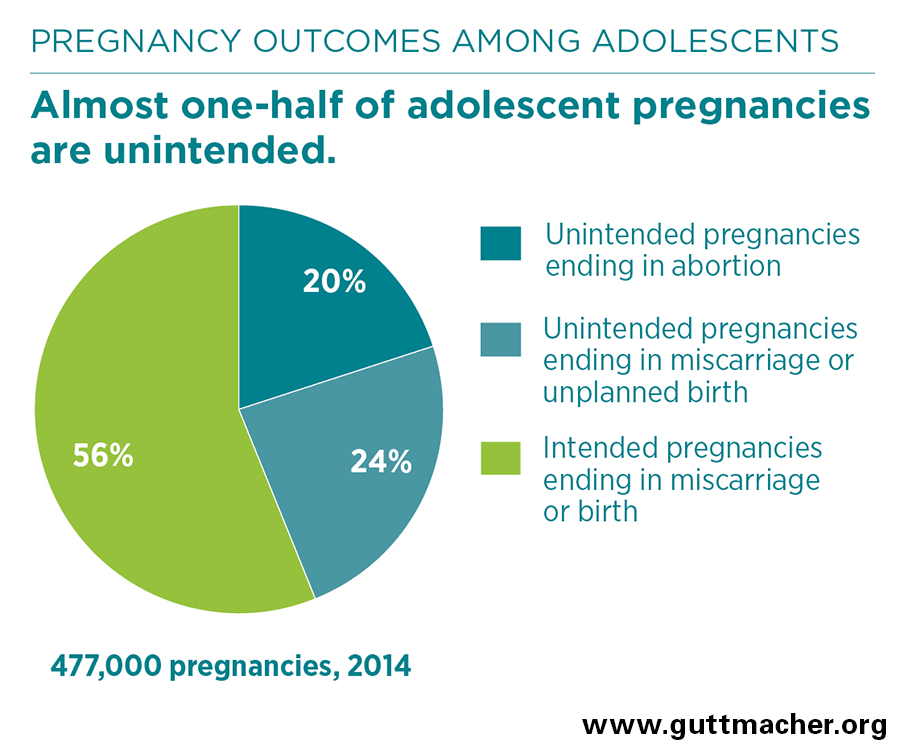

- Globally, most abortions are the result of unintended pregnancy. In Ethiopia in 2014, 44% of pregnancies among adolescents were unintended, and 46% of those unintended pregnancies ended in abortion.

- Among all sexually active women of reproductive age, adolescents had the highest rates of pregnancy and unintended pregnancy (401 and 176, respectively, per 1,000 women).

- The proportion of adolescent pregnancies that were unintended in Ethiopia is comparable to the regional estimate. Nearly one-half of pregnancies among adolescents aged 15–19 in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2016 were unintended, and nearly one-half of these ended in abortion.2

- Meeting adolescents’ contraceptive needs is critical to helping them avoid unintended pregnancies. In Ethiopia in 2016, two in 10 married adolescents and four in 10 unmarried adolescents had an unmet need for contraception—that is, they wanted to avoid pregnancy but were not using a contraceptive method.

Consequences of unsafe abortion

- As of 2014, adolescents in Ethiopia were just as likely as older women of reproductive age to experience severe complications from clandestine abortions.

- An estimated 27% of adolescents seeking postabortion care suffered severe abortion complications, such as sepsis, shock or organ failure.

Implications

- Adolescents in Ethiopia are benefiting from the expanded abortion law that grants them the legal right to obtain safe abortion care. Nevertheless, one-third of abortions among adolescents were clandestine and thus potentially unsafe, according to data from 2014. In the effort to eliminate clandestine and unsafe abortion in Ethiopia, additional research is essential to understand the barriers to obtaining legal abortion care that some adolescents continue to experience.

- Although the Ethiopian government has developed commendable policies aimed at meeting adolescents’ reproductive health needs, further steps toward implementation are required. For instance, targeted programs are needed to improve adolescents’ knowledge of the legal abortion services available to them and to further reduce their unmet need for contraception.

- In addition, because rates of unintended pregnancy are high among Ethiopian adolescents, programs should focus on making certain that family planning services reach all young people, particularly those who are married and less educated, to ensure they have access to the information and services they need to plan whether and when to become pregnant.