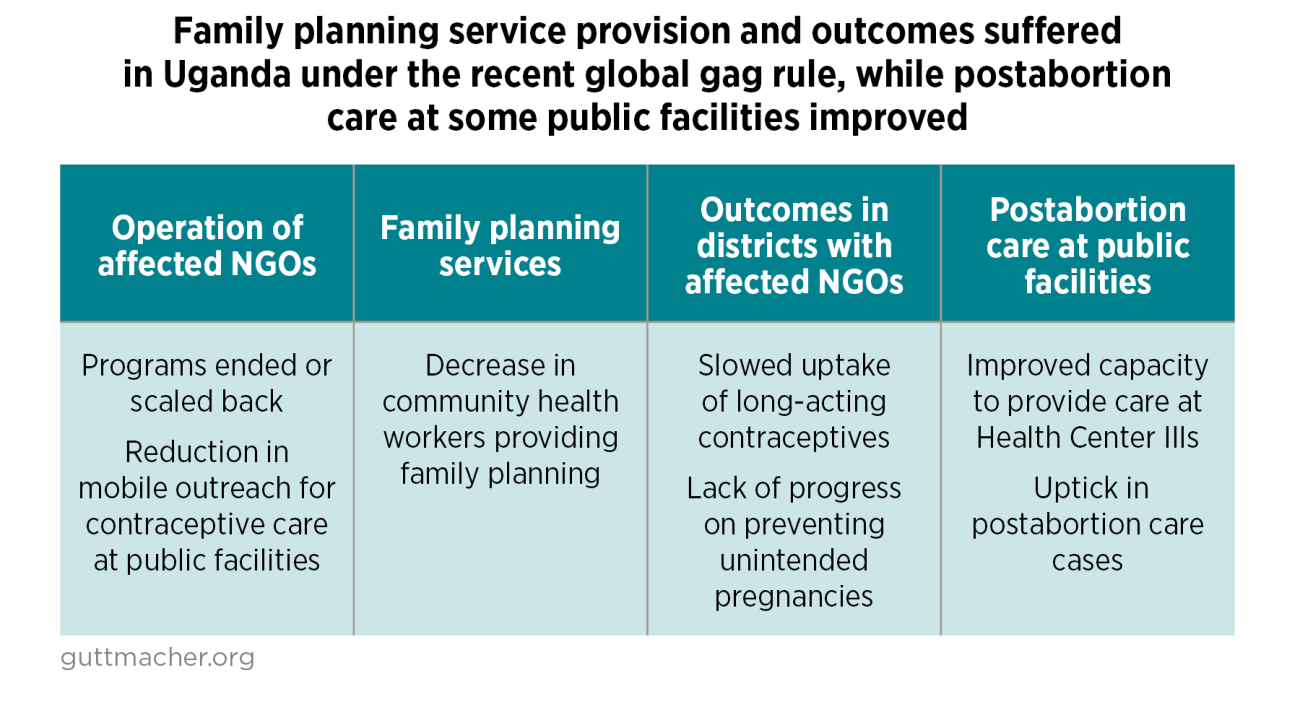

The Trump administration’s “global gag rule,” though now defunct, impinged on gains in sexual and reproductive health in Uganda that were made prior to the policy’s implementation. From May 2017 to January 2021, the policy prohibited US global health funding for non-US NGOs that provide abortion services; offer abortion information, counseling or referrals; or advocate abortion liberalization. Versions of the global gag rule have been repeatedly instated by US presidents from the Republican party and rescinded by Democratic presidents since 1984.

This fact sheet presents findings from a longitudinal study that used a quasi-experimental design to assess the impacts of the recent global gag rule on sexual and reproductive health service delivery and outcomes in Uganda. Changes in service delivery between 2017 and 2019 were assessed using data from 287 health facilities (223 of which were public) that provide family planning services, and changes in women’s health outcomes between 2018 and 2019 were assessed using data from a community-based panel of 2,755 women of reproductive age (15–49).