This fact sheet presents new evidence from a study conducted in Nairobi, Mombasa and Homa Bay counties in 2015. Data were collected in 78 schools from teachers, principals and students in Forms 2 and 3, as well as from key informants involved with policy and program development and implementation.

The need for comprehensive sexuality education

- Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) is necessary to ensure healthy sexual and reproductive lives for adolescents. It should include accurate information on a range of age-appropriate topics; should be participatory; and should foster knowledge, attitudes, values and skills to enable adolescents to develop positive views of their sexuality.1,2

- CSE programs that focus on human rights, gender equality and empowerment, and that encourage active engagement among participants, have been shown to improve knowledge and self-confidence; positively change attitudes and gender norms; strengthen decision-making and communication skills and build self-efficacy; and increase contraceptive use among sexually active adolescents.

- Twenty-six percent of the students in our sample (mostly aged 15–17) had already had sex—42% of males and 15% of females.

The CSE policy and program environment

- In 2013, the Kenyan government signed a declaration in which it committed to scaling up comprehensive rights-based sexuality education beginning in primary school.3

- A major challenge has been to reconcile rights-based approaches to providing information and services to adolescents with conservative approaches that oppose certain aspects of CSE, such as improving access to condoms.

- Education-sector policies have largely promoted HIV education and focused on abstinence, resulting in a limited scope of topics offered in school.

- Life skills—the subject into which the widest range of topics are integrated—is not examinable, and hence there is little incentive for students and teachers to give these topics high priority.

Exposure to sexuality education

- While 86% of adolescents attend primary school, only 33% continue on to secondary school. Most students in Forms 2 and 3 (96%) had received some sexuality education by the time they completed primary school, but the information received at this level is very basic and does not include information on safe sex.

- The majority of students (65%) who started learning in primary school were satisfied with the timing of first exposure, 31% would have liked to have started learning earlier, and 67% of students wanted more hours dedicated to sexuality education topics.

- Almost all students (93%) considered sexuality education useful or very useful in their personal lives. Nearly a third (30%) reported that they did not receive this information from their parents.

Content of curricula and teaching methods

- Messages conveyed are often conservative and focused on abstinence. In their classes, six in 10 teachers strongly emphasized that sex is dangerous and immoral; two-thirds strongly emphasized that abortion is immoral.

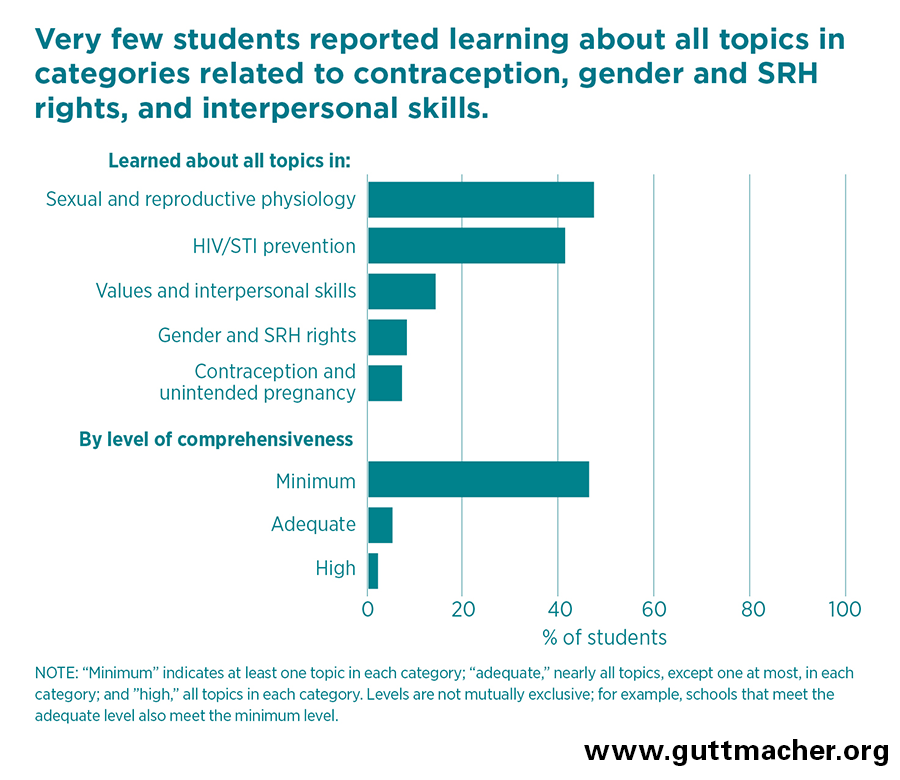

- According to teachers, three-fourths of schools cover all topics that constitute a comprehensive curriculum. However, only 2% of students reported learning about all of them; students said that the most emphasis is placed on reproductive physiology and HIV/STI prevention (Figure 1; topics are listed in the full report).

- According to both teachers and students, less emphasis is placed on gender equity and rights, as well as pregnancy prevention, particularly regarding communication and practical skills related to contraceptive use.

- Most teachers (91%) covered abstinence in their classes, and 71% of these emphasized that it is the best or only method to prevent STIs and pregnancy.

- While 83% of teachers reported covering contraceptives, only 13–20% of students said they learned about different methods, how to use them or where to get them (and more than 60% of students would like to learn more).

Teacher training

- Although 85% of schools required teachers to have pre-service training on such topics, only 70% of teachers in these schools had received it. Just 8% of principals perceived this training to be very adequate, and 68% of teachers felt they needed more training.

- Fewer than half of teachers (46%) had received any in-service training on sexuality education, and only 31% had received such training in the past three years.

- Among teachers who received either pre-service or in-service training, only 36% were trained on all topics that constitute a comprehensive curriculum.

- The main barriers to teaching sexuality education reported by teachers were lack of teaching materials, time or training, and embarrassment about certain topics.

- Nearly half of teachers (45%) felt unprepared or uncomfortable answering students’ questions on sexuality education, and a similar proportion of students reported feeling embarrassed, despite being excited to learn about the topics. Teachers wanted more information and training, particularly on violence prevention, contraceptive use and positive living for people living with HIV.

Classroom environment

- Despite policies aimed at promoting a safe and supportive environment, 76% of students either never or only sometimes felt safe expressing themselves in front of others at school, 52% feared being teased and 34% feared physical harm.

- Teachers held negative attitudes about homosexuality, premarital sex and abortion: Ninety-six percent believed that relationships should only be between a man and a woman, 92–93% believed that females and males should avoid sex until marriage and 61% said that abortion should not be allowed.

- Teachers also held misconceptions about a range of issues related to adolescent sexuality, such as the belief that making contraceptives available encourages young people to have sex (62%).

Recommendations

- In line with the 2013 ministerial declaration, a comprehensive and rights-based focus to sexuality education should be prioritized at the primary school level to ensure that students receive essential age-appropriate information and skills prior to initiating sexual activity.

- Effective coordination between stakeholders is needed to develop and implement policies, guidelines and curricula based on the evidence documenting characteristics of successful CSE programs.

- A wider range of sexuality education topics should be integrated into life skills classes, and this subject should become an examinable part of the curriculum.

- The comprehensiveness of the curriculum content should be improved and teaching methods diversified to reflect international CSE guidelines—with more emphasis on promoting practical skills, confidence and agency; less reliance on fear-based and moralistic messages; and increased focus on pregnancy prevention strategies that cover a broad range of contraceptives and negotiating skills within relationships.

- Teacher training should be prioritized, including attention to in-service training for updating skills and techniques, to ensure that teachers have the information, support and resources necessary to confidently and effectively teach sensitive topics.