Conservative policymakers have made private insurance coverage for maternity care a surprisingly high-profile target in their efforts to roll back health care advances made possible by the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA included a requirement that private plans sold to individuals and small employers must cover 10 categories of essential health benefits, one of which is "maternity and newborn care." That provision closed several loopholes in the decades-old Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978, which had long required such coverage for most people with employer-sponsored health insurance.

As conservative lawmakers in the U.S. House of Representatives debated and approved their version of the American Health Care Act—legislation to undermine or repeal key pillars of the ACA—they included a provision allowing states to rewrite what constitutes "essential health benefits," with maternity care cited by numerous conservatives as something that not all insurance plans should be required to cover. If this attempt to reverse the ACA requirement were to succeed, everyone would lose.

Maternity coverage and care promote the health of women and children. Simply put, the often joyous event of having a child poses considerable risks. For women, the risks include hemorrhaging, high blood pressure, blood clots, gestational diabetes and postpartum depression.1,2 Moreover, the United States has a relatively high level of maternal mortality, particularly among black women.3,4 The risks are also real for infants following their birth: More than 23,000 U.S. infants die each year in their first 12 months,5 and pregnancy complications such as preterm delivery can result in a vast array of short- and long-term health problems for children.6

Prenatal, labor and delivery, and postpartum care can help address these dangers. Medical groups, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have guidelines for labor and delivery to avoid and treat complications, and for screening, diagnostic, counseling, vaccination and other services during the prenatal and postpartum periods to promote better maternal health and healthy behaviors. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has specific clinical recommendations for pregnant and postpartum women, including screening for depression, gestational diabetes, hepatitis B, HIV, preeclampsia and syphilis, as well as interventions for breastfeeding promotion and smoking cessation.7

Maternity coverage helps to spread risk and cost across populations and throughout the lifespan. Some critics of requiring health plans to cover maternity care argue that insurance should not have to cover a predictable life event. This criticism misses the point. Everyone benefits at some point in their life from maternity and newborn care. The most recent national estimate found that by age 40, 85% of U.S. women had given birth, and 76% of men had fathered a child.8 And essentially every person has benefited as an infant.

Moreover, pregnancy is not as predictable as critics assert. In 2011, 45% of U.S. pregnancies—2.8 million of them—were unintended.9 And those numbers would be considerably higher without the family planning services that the same conservative policymakers and advocates who are working to cut maternity coverage are also seeking to undermine in numerous ways. Even when a pregnancy is fully planned, a woman may face a wide variety of unexpected and expensive complications. Insurance coverage for maternity care helps to mitigate these difficult-to-predict risks.

Insurance coverage of maternity care makes an expensive event more affordable. Before the ACA was enacted, few states required coverage of maternity care in the individual insurance market, and eight in 10 plans in that market failed to cover maternity care at all.10 Plans might offer coverage for pregnancy only through a separate "rider" that could cost thousands of dollars and might include waiting periods in order to exclude coverage for women who were already pregnant. Those costs and exclusions made sense for insurers from a business perspective, because they assumed that the women most likely to purchase a rider would also be most likely to use it that year, and therefore be expensive for the insurer to cover.

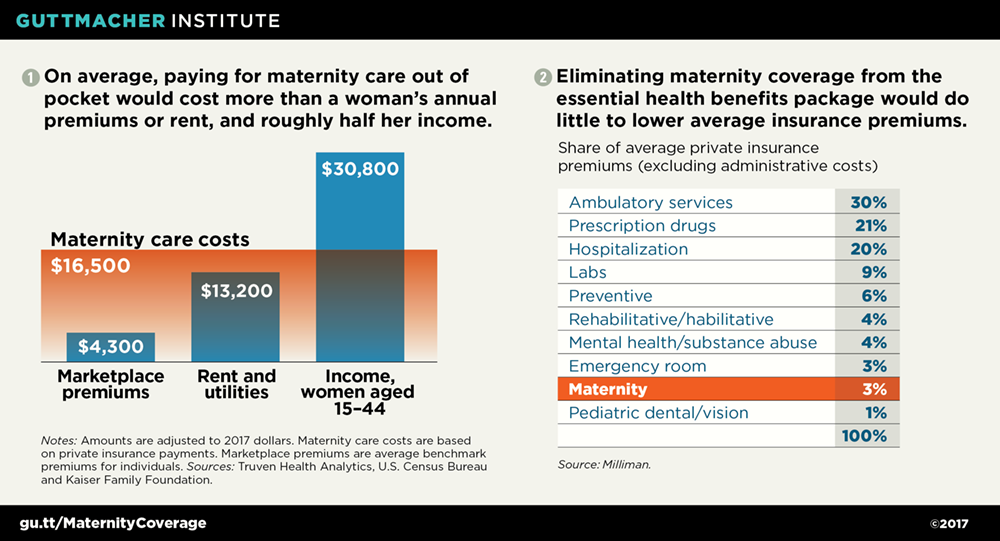

In the absence of this coverage, a pregnancy could result in a daunting, even bankrupting, level of expense for women and families to pay out of pocket—particularly younger women, who are most likely to become pregnant while also least likely to have a steady income or significant savings.9,11 A nationwide study in 2010 found that for women with employer-sponsored insurance, the average payment for a vaginal birth was around $12,500, which would be closer to $15,300 today after adjusting for inflation (see chart 1).11–15 For the one-third of U.S. births that involve a cesarean section,15 those payments were nearly $16,700, which would be close to $20,400 today.12,13 Women with pregnancy complications can face considerably higher costs. For example, nearly 10% of births involve preterm deliveries,16 which one study found to cost 10 times as much as an uncomplicated birth.17

Eliminating required maternity coverage would undermine progress under the ACA. If insurers could exclude or limit maternity coverage in some or all of their individual and small-group market plans, women would face the severe problems and discrimination that existed prior to the ACA’s passage. They might have to make a choice among several bad options: plans that exclude maternity coverage entirely, include long waiting periods for maternity coverage or require thousands of dollars extra in premiums each year.

Many women would end up relying on Medicaid, rather than private insurance, to cover the costs of a pregnancy, because in most states, pregnant women are eligible for Medicaid at much higher income levels than other adults.18 Forcing women to change health plans—and possibly their health care providers—when they become pregnant would undermine continuity of care before, during and after pregnancy. That in turn would undermine maternal and infant health.

Many other women would end up without coverage at all for critical components of their maternity care. Hospitals are required to provide labor and delivery care to anyone in active labor, as part of their obligation to provide emergency care. Yet, these women could be cut off from the array of beneficial prenatal and postpartum services unless they could afford to pay entirely out of pocket—on top of all the other expenses of parenthood.

Making maternity coverage optional would mostly shift costs, not reduce them. A primary rationale for eliminating required coverage of maternity care is that it would supposedly reduce insurance premiums in the individual insurance market. In reality, maternity and infant care combined account for only 3% of premiums, according to a 2017 analysis by the actuarial firm Milliman (see chart 2).19 The vast majority of premium costs are related to outpatient care, prescription drugs, hospital care and other services that few conservatives would suggest be excluded from insurance coverage. So, cutting maternity care would do almost nothing to reduce premiums overall.

By contrast, women forced to buy a separate rider for maternity care or to pay for it out of pocket would face thousands of dollars in additional expenses. The federal and state governments would also likely lose out financially, if pregnant women were forced to shift from private insurance to Medicaid. And hospitals would face a surge in uncompensated labor and delivery care for women who lose maternity coverage entirely.

Broader attacks on Medicaid and private insurance would similarly harm maternity care. Conservatives’ attempts to dismantle the ACA go far beyond the essential health benefits requirement. The House version of the American Health Care Act would effectively phase out the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, place unprecedented caps on federal Medicaid expenditures, and reshape and scale back tax credits that make individual market insurance more affordable, among numerous other important changes.

The end result would be 23 million fewer people with insurance—including comprehensive coverage for maternity care—by 2026, according to the most recent analysis from the Congressional Budget Office.20 The House bill would also provide an option for states to receive Medicaid funds as a block grant, and in the process give states authority to discard decades-old protections for pregnant women and maternity care, among many other provisions of federal Medicaid law. That means the vision that conservatives are articulating for the individual insurance market—one that would increase the health and financial risks surrounding pregnancy, to the benefit of no one—could become reality for millions of U.S. women and their families.