India has made important gains in improving the sexual and reproductive health of women and young people. These advances include the expansion of the contraceptive method mix under the National Family Planning Programme, efforts to strengthen the contraceptive supply chain, and the 2014 launch of the Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (National Adolescent Health Programme), which prioritizes healthy development during adolescence.1,2

Critical gaps in meeting adolescent sexual and reproductive health needs remain. As a result of lack of accurate information, provider bias and other barriers, many adolescents have limited agency to protect and foster their own sexual and reproductive health,3–5 and obtaining comprehensive abortion care can be particularly challenging.4,6,7 Difficulties related to obtaining information and services are compounded for adolescents who are marginalized on the basis of their sexuality, gender expression or marital status.8–10 Gaps in access to comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care must be addressed for all adolescents, so they can exercise their rights to bodily autonomy and lead healthy lives.11–14

The Adding It Up project estimates the need for, impact of and costs associated with increased investment in essential sexual and reproductive health services, including contraceptive care, maternal and newborn health care, and abortion-related care. These estimates demonstrate the immense potential benefits of investments to ensure that young women can decide whether and when to have children and can experience safe pregnancy and delivery. The estimates presented here pertain to adolescent women* aged 15–19 in India in 2019.†

Unless otherwise noted, the estimates in this report come from Sully E et al., Adding It Up: Investing in Sexual and Reproductive Health 2019, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2020, and its accompanying methodology, which contains sources and methodological details. Some of the key data sources for this report include the United Nations (UN) Population Division’s World Population Prospects 2019, for population data; the UN Population Division’s Estimates and Projections of Family Planning Indicators 2020, for unmet need and current contraceptive use data; the Indian National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), for data on subgroup and state-specific service coverage and need; and the Sample Registration System from the Office of the Registrar General, India, for numbers of maternal deaths. Unless otherwise noted, the data in this report come from calculations based on these sources.

Key points: Understanding the need for and impact and cost of sexual and reproductive health services for adolescent women in India

Need

- 2 million adolescent women in India have an unmet need for modern contraception

- 52% of adolescents giving birth make the recommended minimum of four antenatal care visits

- 78% of abortions among adolescents are unsafe and thus carry an elevated risk for complications

- 190,000 adolescents do not receive needed care following an unsafe abortion

Impact

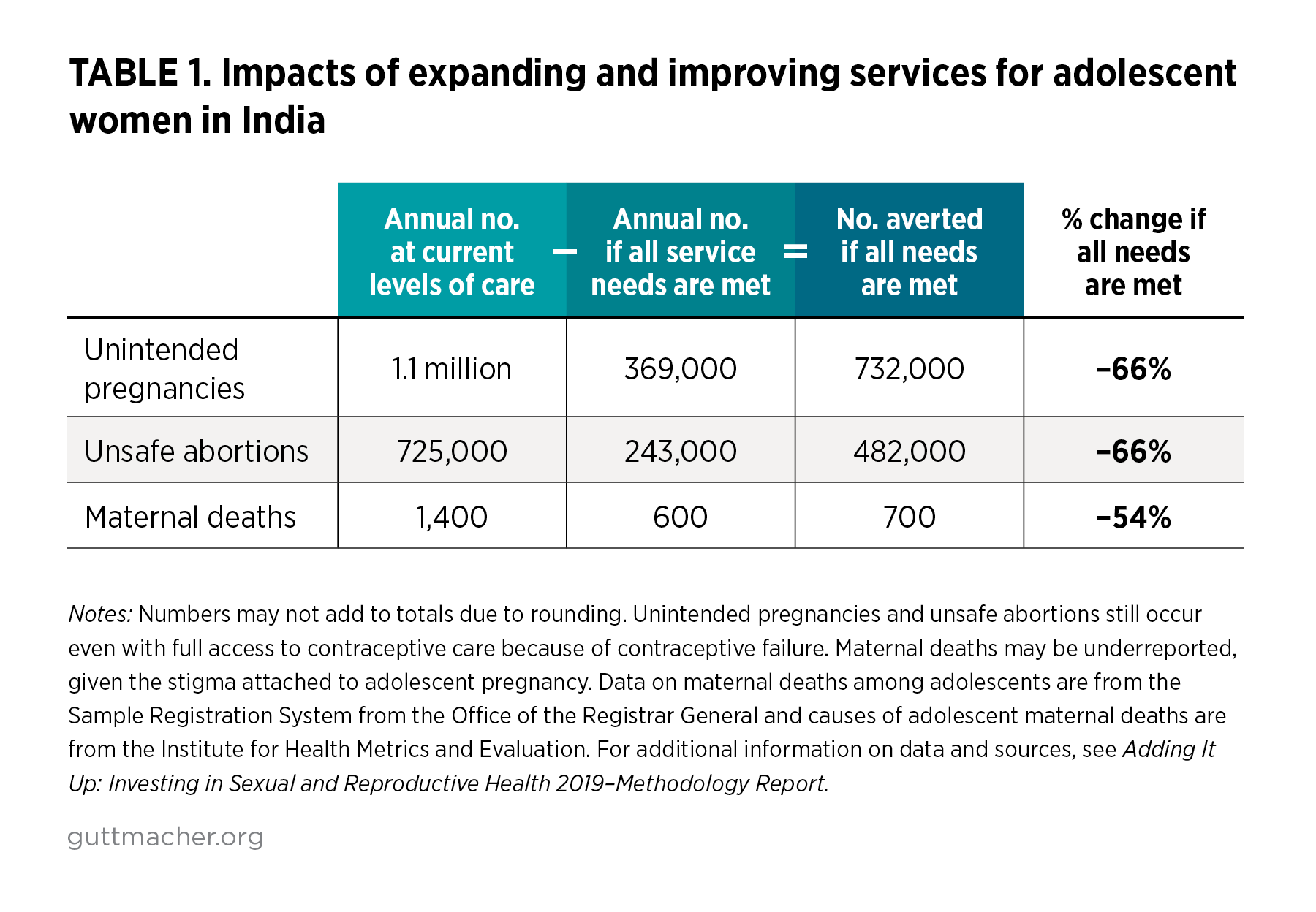

If all adolescent women in India wanting to avoid a pregnancy were to use modern contraceptives and were provided the full spectrum of contraceptive options, counseling and information, and if all needs for maternal, newborn and abortion-related health care were met, annually there would be:

- 732,000 fewer unintended pregnancies

- 482,000 fewer unsafe abortions

Cost

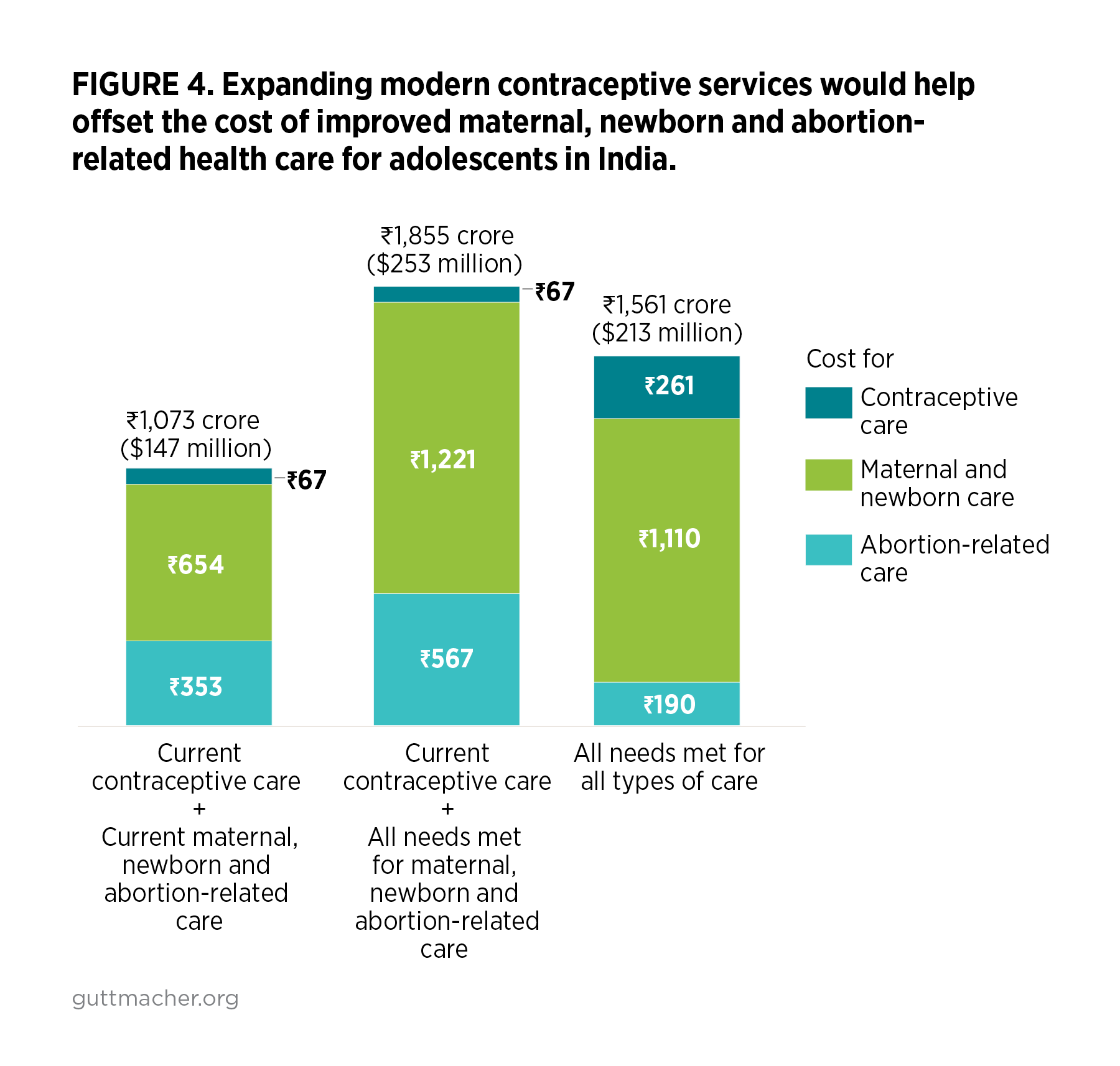

Providing contraceptive care, maternal and newborn health care, and abortion-related care to all adolescent women in India who need these services would cost ₹11.42 (US$0.16) per capita annually. This includes both the direct costs of providing care and the indirect costs associated with programs and systems.

Need for contraceptive services

In India, many women become sexually active, marry and start childbearing between the ages of 15 and 19. Many adolescent women—3.4 million—want to avoid pregnancy. This includes 3.2 million married women and 195,000 sexually active unmarried women.‡

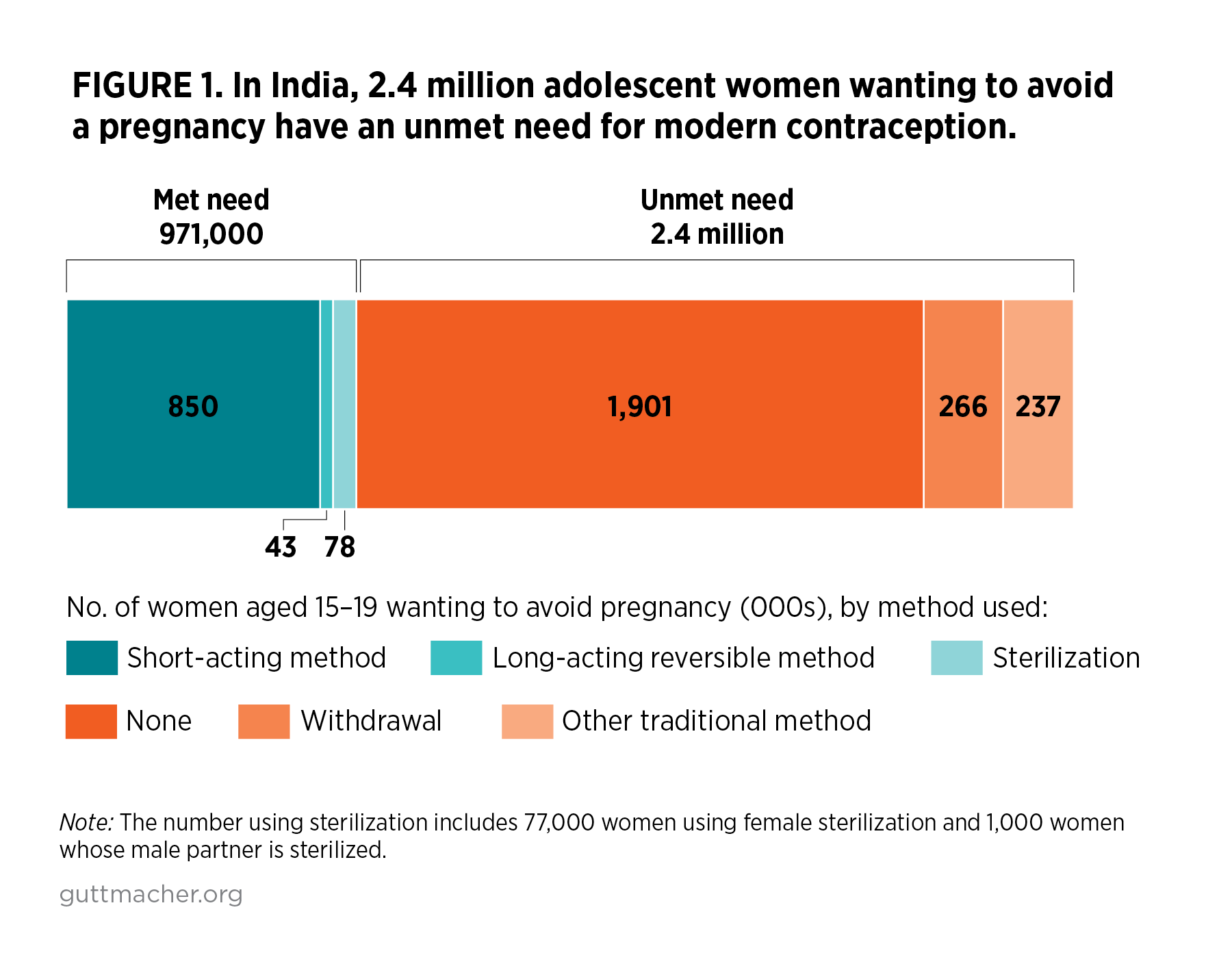

- Among adolescent women wanting to avoid a pregnancy, only about one million (29%) are using modern contraceptive methods (Figure 1).

- About half (48%) of adolescent women and their partners who use modern methods rely on male condoms. Forty percent use other short-acting methods including 37% who use the oral contraceptive pill and 3% who rely on either injectables, lactational amenorrhea or female condoms. These methods are predominantly obtained from the private sector.15 Eight percent of adolescent women using modern methods use permanent female sterilization, and 4% use long-acting reversible methods.

- More than two million adolescent women wanting to avoid a pregnancy (71%) do not use a modern contraceptive method and are therefore categorized as having an unmet need for modern contraception. The majority of these adolescents use no method at all, while about 10% of them use withdrawal as their primary form of contraception.

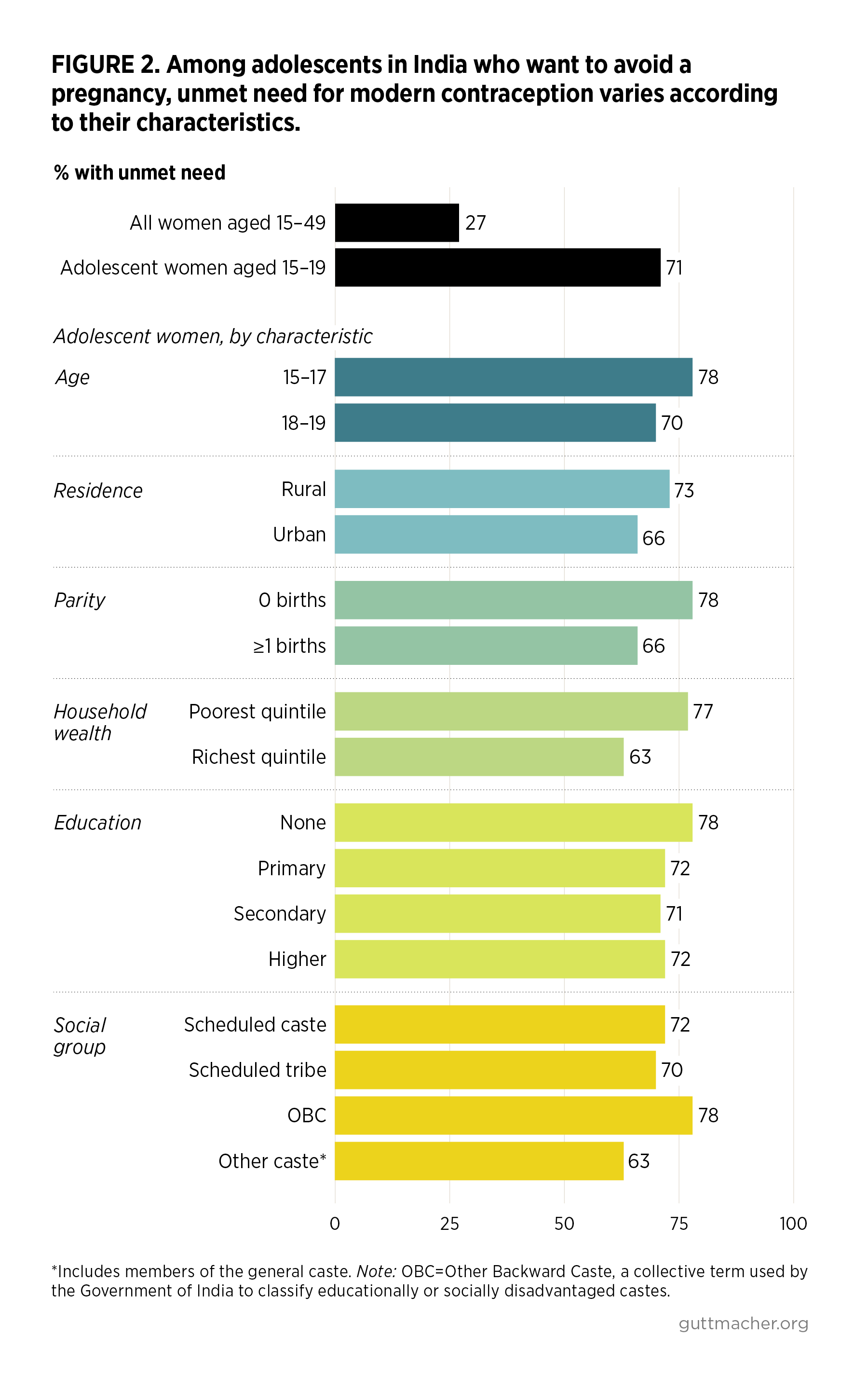

- Among women wanting to avoid a pregnancy, the proportion who have an unmet need for modern methods is much higher for adolescents (71%) than for all women in India of reproductive age (27%).

- The level of unmet need for modern contraception varies across groups of adolescent women wanting to avoid a pregnancy. For instance, unmet need affects 63% of adolescents from the richest households and 77% of those from the poorest households (Figure 2). Unmet need is also elevated among adolescent women in rural areas, those who have not begun childbearing and those younger than 18.

- Of the 60 million adolescent women in India, two million each year experience a pregnancy. The majority of these pregnancies (63%) are unintended, meaning they occur too soon or are not wanted at all. Adolescent women with an unmet need for modern contraception account for nine out of every 10 unintended pregnancies among 15–19-year-olds.

Need for maternal and newborn health care

Although relatively high proportions of adolescent women giving birth do so in a health facility (85%; Figure 3) and deliver with a skilled birth attendant (86%), there are still many adolescents whose needs for pregnancy-related health care are not being met, and these gaps vary according to women’s characteristics.