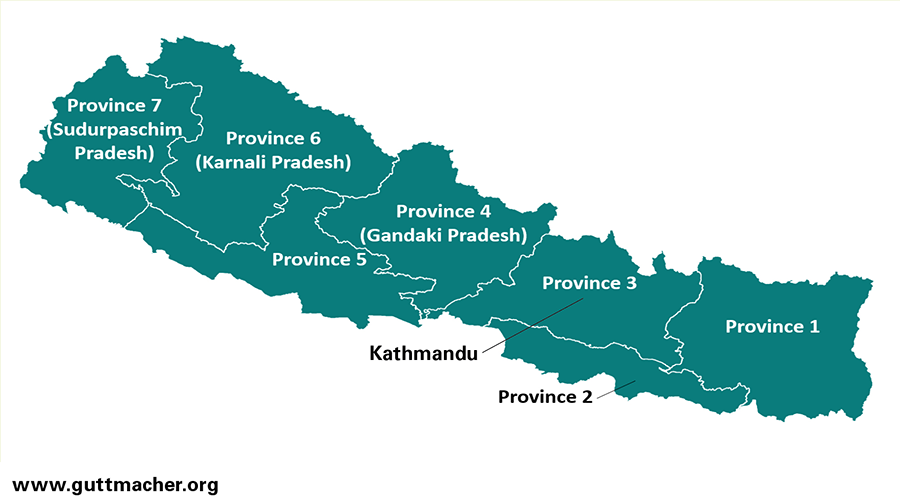

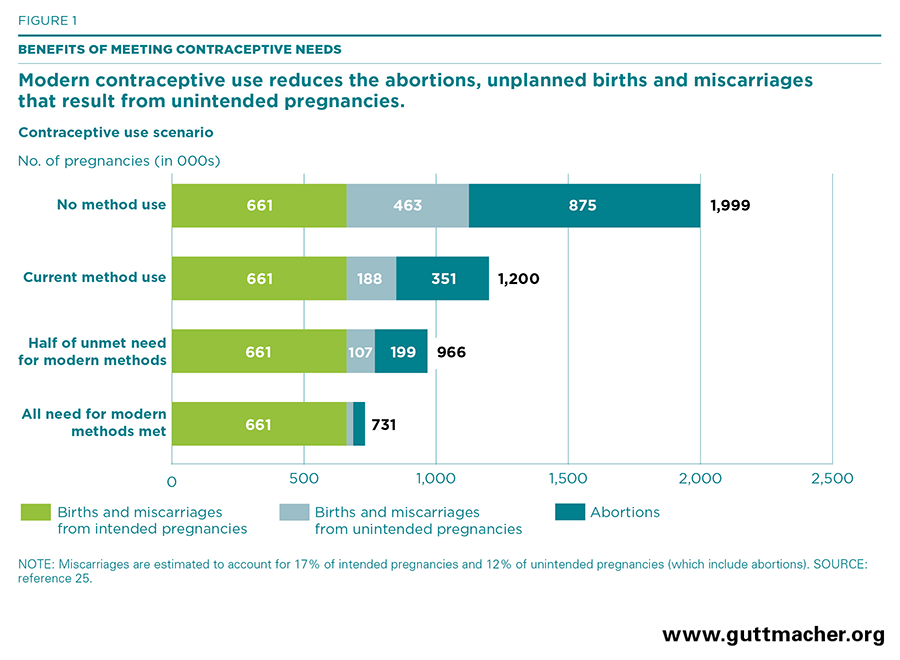

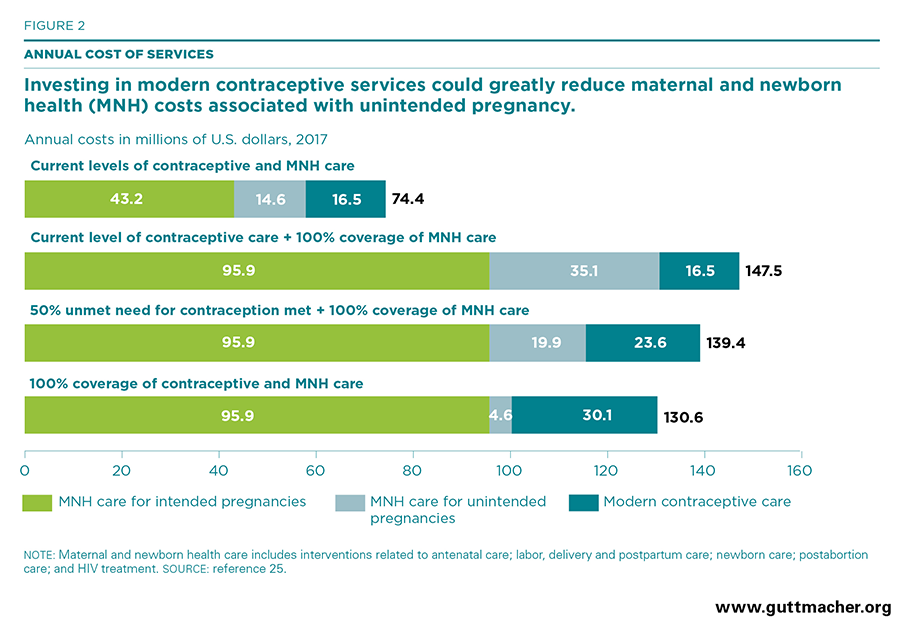

This report examines the need for and costs and benefits of expanding sexual and reproductive health services in Nepal in two key areas: modern contraceptive services and maternal and newborn health care. Estimates are presented at both the national and subnational levels.

Corrected June 10, 2019. See note below.