- Publicly funded family planning clinics provide critical contraceptive, sexual and reproductive health and other preventive health services to poor and low-income women.

- Between 2010 and 2015, the proportion of these clinics offering a wide range of contraceptive methods on-site, especially long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods, increased significantly. More than half (59%) of clinics met the Healthy People 2020 objective of offering the full range of contraceptive methods.

- Along with increased method provision, between 2010 and 2015 clinics were more likely to offer same-day appointments, to have shorter wait times for an appointment, and to have protocols in place that facilitate initiation and continuation of oral contraceptives and LARC methods for women who choose them, including offering “quick-start” and delayed pelvic exam protocols for new oral contraceptive users. Clinics were also more likely to offer noncontraceptive services in 2015, such as primary care services, diabetes screening and mental health screening.

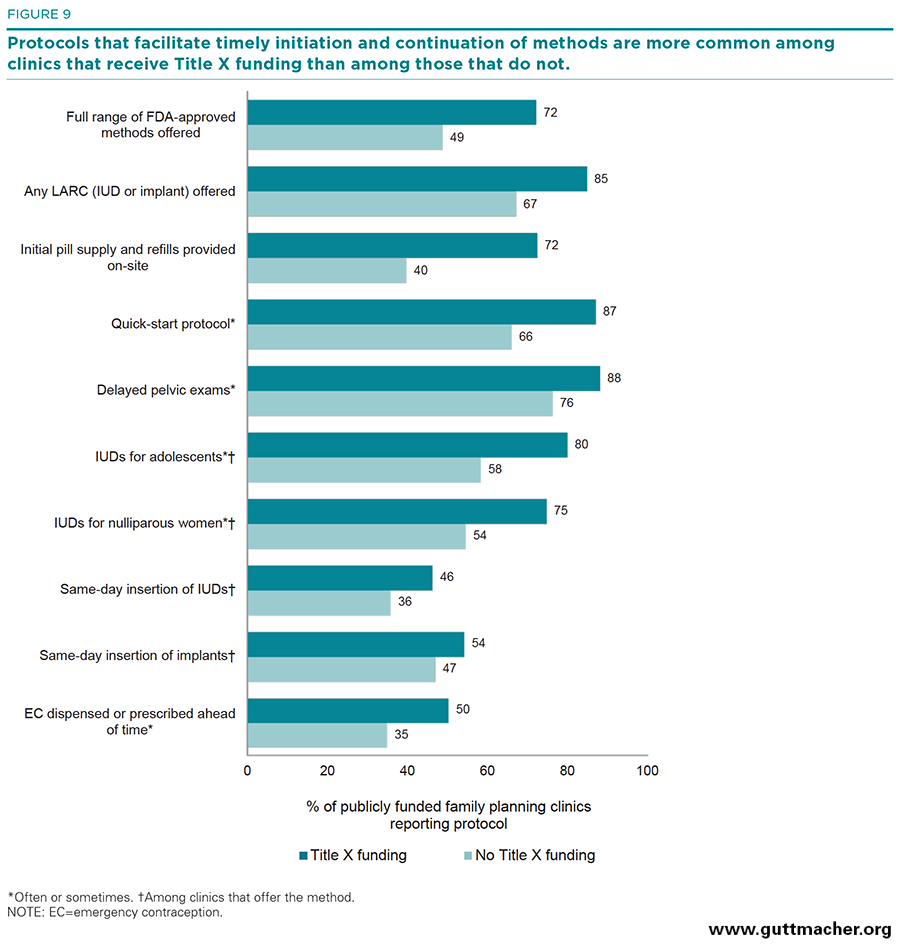

- Clinics that receive at least some funding through the federal Title X program were more likely than clinics that do not receive such funds to offer a wider range of contraceptive methods on-site and to have protocols that facilitate initiation and continuation of oral contraceptives and LARC methods, including dispensing oral contraceptive supplies at the clinic and same-day insertion of IUDs and implants.

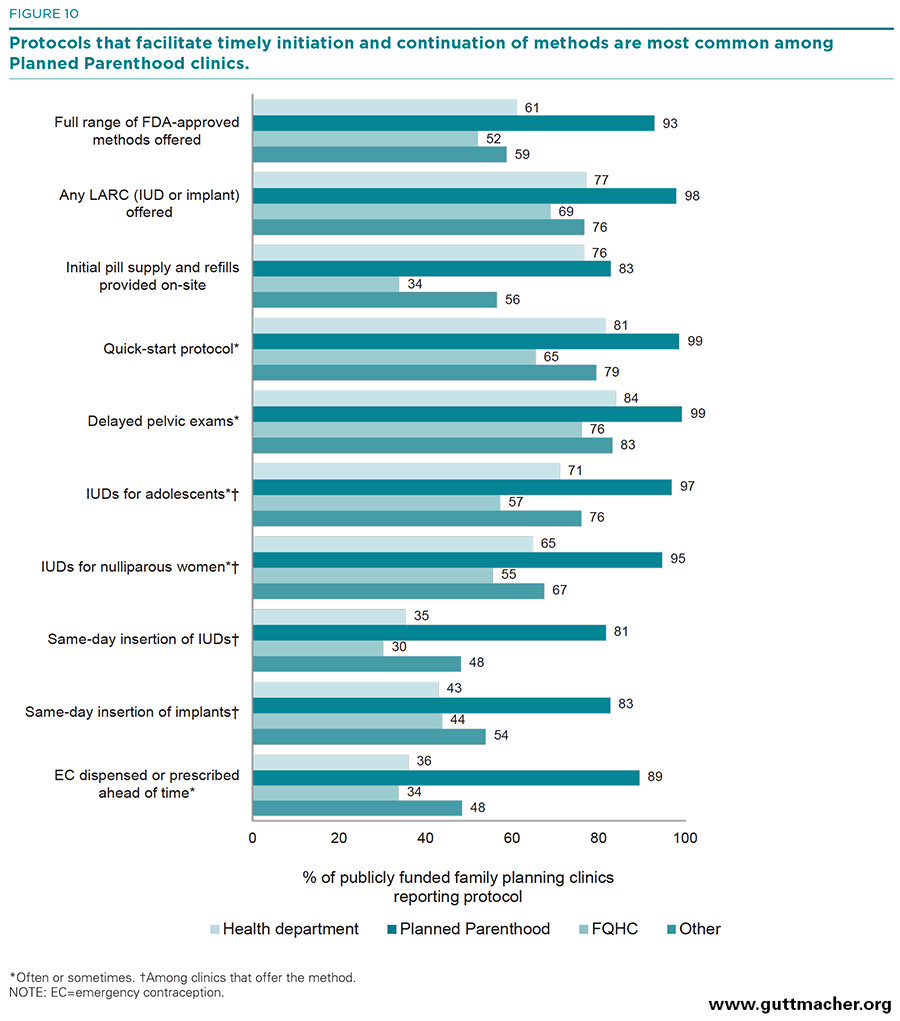

- Planned Parenthood clinics were significantly more likely than any other clinic type to have implemented a variety of protocols that enhance contraceptive method initiation and continuation.

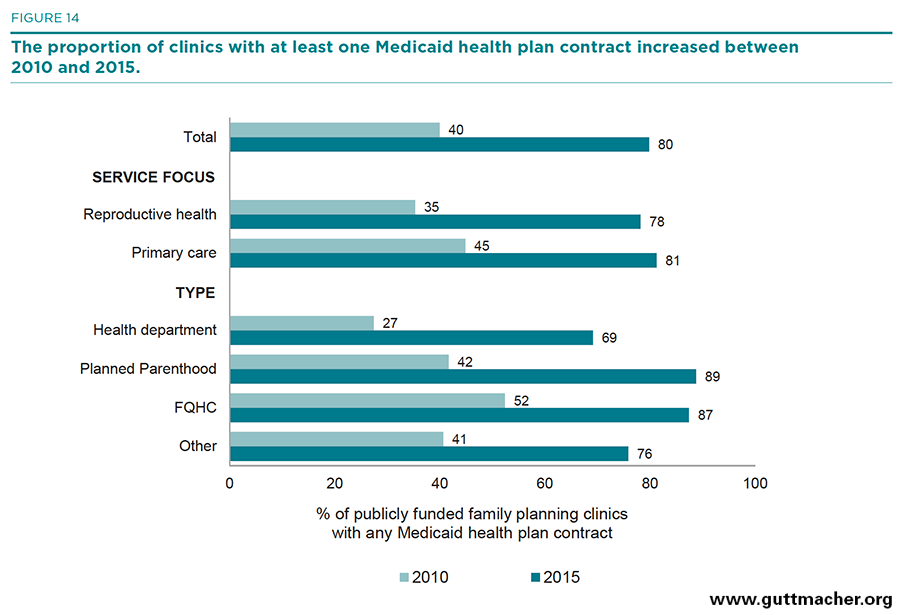

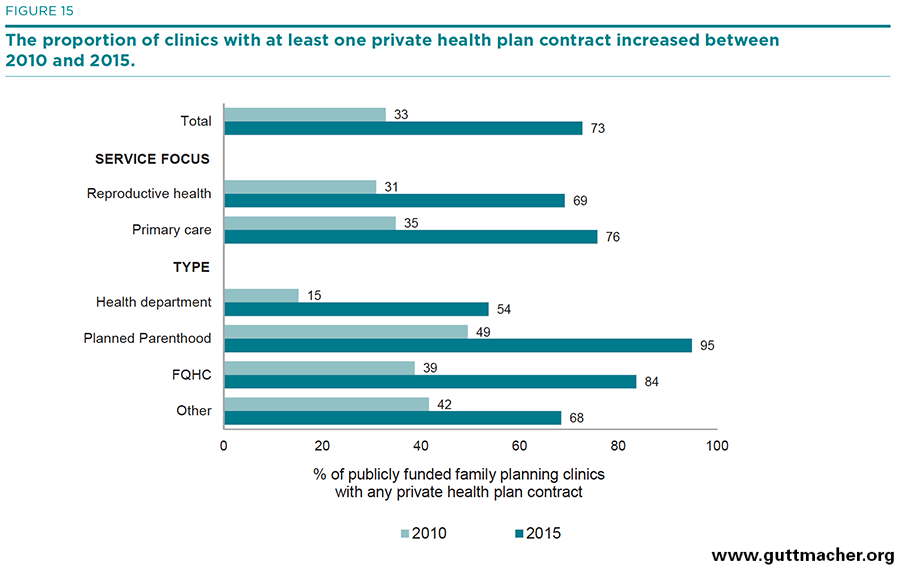

- Between 2010 and 2015, the proportion of clinics reporting contracts with private health plans and with Medicaid at least doubled, indicating a rapid ramping-up of clinics’ ability to function successfully in the new health care marketplace.

Publicly Funded Family Planning Clinics in 2015: Patterns and Trends in Service Delivery Practices and Protocols

Key Points

Background and Significance

Publicly funded family planning clinics—including public health department and Planned Parenthood clinics, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), and other community and hospital outpatient sites—provide millions of women with critically important contraceptive and related reproductive health services each year. In 2014, some 5.3 million American women received contraceptive services from a publicly funded clinic.1 In fact, more than one-quarter (27%) of all U.S. women who receive contraceptive services—and 44% of all poor women—receive that care from a publicly funded family planning clinic.2 In addition to contraceptive services, these clinics provide women with a wide range of preventive health services, testing and treatment for STIs, and referrals for other needed care.3 In many cases, publicly funded family planning clinics provide the only regular health care women receive.2 Moreover, care from publicly funded clinics allows women to plan the timing of wanted pregnancies and to avoid unintended pregnancies—they helped women to avoid some 1.3 million unintended pregnancies in 2014 alone. Clinic services to diagnose and treat sexually transmitted infections help to prevent tens of thousands of chlamydia and gonorrhea cases each year and cervical cancer screening help to avert thousands of cancer cases.4

Understanding the range of services provided by the publicly funded clinic network, as well as variation among different types of clinics in both services offered and protocols followed when dispensing care, is important for the development of evidence-based policies and programs aimed at ensuring access to contraceptive and other reproductive health care services for the millions of poor and low-income women who need them. Given recent changes in health care financing and delivery, including those related to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), it is even more important to closely monitor trends in the care being offered by different types of providers. The Guttmacher Institute has a long history of monitoring the number and location of publicly funded family planning clinics3,5–12 and conducting sample surveys to better understand and document the clinic network’s range of service delivery practices and the challenges it faces.13–17 Most recently, in 2010,3 a nationally representative sample of 1,839 publicly funded family planning clinics was surveyed and information was collected in a variety of key areas, including

- types of contraceptive methods and other health services offered on-site and through referral;

- service delivery practices and protocols, particularly those that have the potential to affect service accessibility, method initiation and continuation;

- clinic scheduling patterns;

- types of service agreements with other clinics within the community;

- insurance coverage among clients; and

- other measures of clinical practice and management.

In 2015, a similar study was designed and conducted to provide updated information on many of the same measures. This report presents the results from this nationally representative survey of a sample of publicly funded family planning clinics, focusing on trends between 2010 and 2015 and looking at variation across clinics according to their principal service focus (provision of contraceptive and reproductive health care services or comprehensive primary care services), their Title X funding status (funded or not) and their administrative type (health department, Planned Parenthood, FQHC or other). For some measures, we also examine whether there are differences across clinics according to whether the clinic is located in a state that had implemented either a Medicaid expansion under the ACA or had a Medicaid family planning expansion in effect during 2015; such expansions allow states to increase the number of women who receive Medicaid-funded care based on their income level.

The publicly funded family planning clinic network comprises more than 8,000 sites located throughout the country.6 This loose network of providers includes all sites that offer contraceptive services to the general public and use public funding, including Medicaid, to provide free or reduced-fee services to at least some clients. These clinics are run by a variety of types of administrative entities. Some are linked to larger county, state or national organizations, while others are independent community providers. In 2010, state or county public health departments administered 29% of all clinics and served 27% of all clients receiving care from this network of providers.6 Planned Parenthood affiliates administered 10% of clinics, but served more than one-third of the clients (36%). The remaining clinics were administered by FQHCs (38%), serving 16% of clients; or by other types of agencies (16%), serving 13% of clients. Hospital outpatient clinics account for 8% of the network and make up the largest single clinic type within the "other clinics" category. Groups too small to report separately include independent women’s clinics, other community clinics not part of the FQHC network (such as FQHC look-alikes*), Indian Health Service clinics and other unaffiliated clinics.

The federal Title X family planning program sets the standards that unify about half of all publicly funded family planning clinics. For over four decades, Title X has served as the only federal program devoted to providing family planning services to low-income and underserved women; the program funded contraceptive services at some 4,100 clinics in 2014.18 Title X–funded clinics serve more than two-thirds of all clients receiving care from the network of publicly funded family planning providers, and more than half of all Title X clinics are run by public health departments.6 Title X provides flexible funding that can be used for direct patient care, as well as infrastructure, outreach or educational services. Critically, Title X also provides clinical guidelines that set the standard of care for all clinics that receive at least some financial support through the program; in 2010, 70% of all family planning clinic clients were served in sites that receive some Title X funding.6 Title X–funded clinics adhere to ethical standards about patient confidentiality and the provision of voluntary services, and they follow guidelines about the provision of a wide range of contraceptive methods and related preventive health services for all clients.

Our assessment of clinic performance compares clinics according to Title X funding status and type, providing evidence of the added benefit that is derived from Title X funding and the wide variation in care provided by different provider types. These findings are important for program planners and policymakers seeking to ensure that all women and couples, regardless of their income or insurance status, are able to receive the contraceptive and preventive care they need to avoid unintended pregnancies and plan for wanted births. These data are especially critical given the challenges and changes brought about by transitions in health care financing and delivery. Moreover, they can be used to inform the ongoing debate about the benefits of public funding for contraceptive services by providing accurate, up-to-date information about the full range of preventive and diagnostic services offered by the clinic network.

Methodology

Sample

Between February and November 2015, we surveyed a nationally representative sample of 1,839 clinics providing publicly funded contraceptive services. The sample was drawn from the 8,497 eligible publicly funded family planning clinics included in the Guttmacher Institute’s list of all publicly funding family planning clinics. Using directories of Title X–supported clinics, Planned Parenthood affiliates, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and Indian Health Service units, as well as personal communications with Title X grantees, agency administrators and others, this list is regularly updated to confirm clinic names, addresses, public funding status and provision of contraceptive services.

Sampled clinics were stratified by type (health department, Planned Parenthood, FQHC and other) and whether they received any Title X funding. Clinics were randomly selected within each of the eight resulting categories. Because there are many more clinics of some types than of others, we varied the proportion of each type that was sampled to ensure a sufficient number of cases to make estimates specific to each type. We randomly sampled 37% of Planned Parenthood clinics, 18% of FQHCs, 19% of health departments, and 25% of hospitals and other facilities.

Fieldwork protocols

Surveys were pretested with clinic administrators and were then mailed to clinic family planning directors in February and March 2015. The eight-page questionnaire asked for basic information about the clinic, including client caseload and staffed hours, and about the range and type of contraceptive services provided. Questions addressed current reproductive health services provided (or offered through referral), clinic practices and protocols regarding services offered, referral relationships with other providers, and contracts with public and private health insurance plans.

A reminder mailing was sent to clinic administrators in April. To improve the response rate, follow-up phone calls and e-mails were made to nonresponding facilities between April and November 2015. Over 7,600 contacts were made during this period, via phone, e-mail and fax. To improve the response rate, clinics that had not yet responded to the survey within five months after the initial mailing were offered a $25 incentive for completed surveys, and letters announcing the incentive were mailed directly to the contact person identified as most appropriate during nonresponse follow-up; 420 clinics responded to the incentive offer.

Response

Ultimately, 867 clinics responded to the survey, 15 clinics refused and 871 never responded, even after multiple follow-up attempts. (The original sample included 86 clinics that were found to be ineligible, primarily because they had closed or had stopped providing family planning services at the site due to administrative changes or loss of funding. These clinics were not replaced in the sample.) In addition, some clinics in the original sample were found to be "satellite" sites, i.e., sites that were open less than two days per week and where family planning services were provided by staff from another full-service site in the same agency. In most of these cases, we replaced the satellite site in the sample with another site in the same agency that was not a satellite. The overall response rate among eligible clinics was 50%, and the rate among Title X clinics was 65%. Response by provider type (regardless of Title X status) was 70% among Planned Parenthoods, 63% among health departments, 37% among FQHCs and 41% among others.

Key measures

We present data on key clinic characteristics and variation in services and protocols according to the following characteristics:

- Principal service focus, measured as reproductive health versus primary care or other non–reproductive health

- Title X funding status, measured as Title X funded or not

- Clinic type, measured as health departments, Planned Parenthood clinics, FQHCs or "other" clinics (a category that comprises clinic types whose totals are too small to be analyzed separately)

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22. All cases were weighted for sampling ratios and nonresponse to reflect the universe of family planning providers at the time the sample was drawn. Comparisons between clinics according to their key characteristics have been tested for significance using independent group t tests, and significance is reported for all comparisons at p<.05. All comparisons that are mentioned in the text are statistically significant at p<.05. However, not all significant comparisons have been mentioned in the text, as the purpose of this report is to highlight those comparisons that illustrate wide differences among groups or those that have policy implications or other substantive importance. The text tables indicate all the significant comparisons and are available for anyone interested in that level of detail.

Appendix A includes further detail for most of the survey items; however, significance testing has not been performed for this table. Appendix B is the full questionnaire.

Clinic Characteristics and Logistics of Obtaining Care

In the United States, publicly funded family planning services are administered by a diverse network of provider agencies. These agencies provide services at more than 8,000 clinics nationwide. In this section, we compare clinics according to several key characteristics, including their principal service focus, Title X funding status, size and location, as well as how these characteristics vary according to type of provider. Because contraceptive visits are often time sensitive, we also look at variation in service hours and scheduling across clinic types. Same-day appointments increase a woman’s ability to obtain a contraceptive method in a timely manner, which may reduce her risk of unintended pregnancy. Offering extended hours during evenings and weekends also facilitates access, which may be particularly important for poor and low-income women, who are less likely than other women to have flexible schedules that allow for doctor’s visits during typical weekday work hours.

Principal service focus

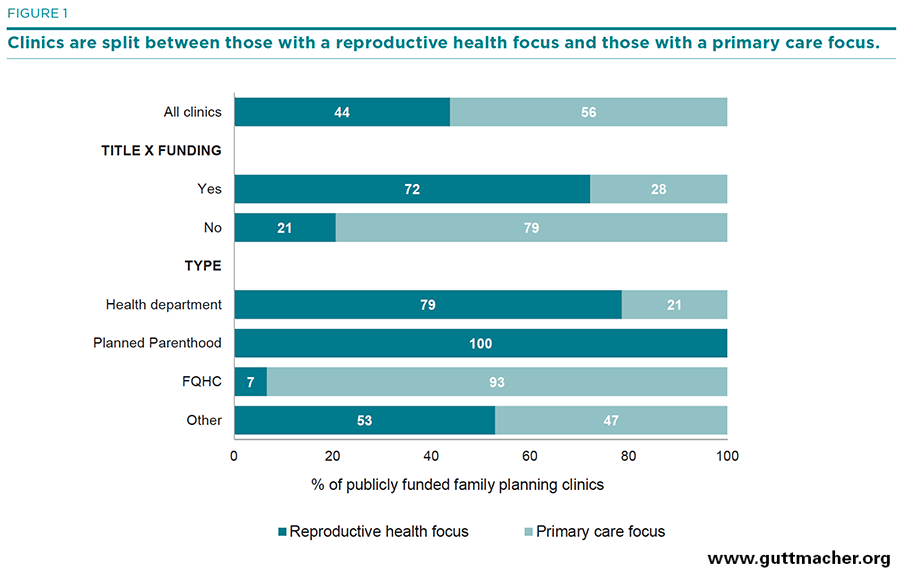

Four in 10 (44%) publicly funded family planning clinics reported being specialized reproductive health care providers whose principal service focus is providing family planning and related sexual and reproductive health services (Figure 1, and Table 1). Nearly six in 10 (56%) clinics reported having a general health or primary care focus, providing contraceptive services along with a broad range of health care services. Throughout this report, we make comparisons between these two groups of clinics—those whose principal service focus is on family planning and sexual and reproductive health care and those with a general or primary care focus—with the hope of better understanding some of the benefits and weaknesses of different delivery models in meeting the needs of U.S. women.

The vast majority of health department sites (79%) and all Planned Parenthood sites focused on reproductive health, as did about half (53%) of sites in the "other clinics" category. In comparison, only 7% of the FQHCs reported being focused on the provision of reproductive health services. Given the fact that most FQHCs are primary care providers, it may be surprising that any reported a reproductive health focus. However, in some cases, family planning clinics had secured FQHC funding or were affiliated with or operated by an FQHC network but retained their focus on family planning.

Title X funding status

Forty-five percent of all publicly funded clinics providing contraceptive care received some funding from the federal Title X program. This status varies widely by provider type: 86% of health department and 69% of Planned Parenthood clinics receive Title X funding, compared with 17% of FQHCs. Nearly three-quarters (72%) of Title X–funded sites reported being focused on providing reproductive health services.

Clinic location

Over the last two decades, many states expanded eligibility for Medicaid coverage of family planning services. As of February 2015, 25 states had initiated broad income-based expansion programs to provide family planning services under Medicaid to individuals with incomes well above the cut-off for Medicaid eligibility overall and regardless of whether they meet other requirements for Medicaid coverage, such as being a low-income parent.19 In addition, under the ACA, 28 states had expanded eligibility for full-benefit Medicaid by February 1, 2015. In combination, at the time of our survey, a total of 40 states and the District of Columbia† had in effect either an ACA full-benefit Medicaid expansion or a family planning–specific Medicaid expansion, or both. Eighty-two percent of clinics were located in such jurisdictions. There were no significant differences by type, Title X funding status or service focus between clinics located in expansion or non-expansion states.

Client caseload

About half of clinics (47%) reported serving fewer than 20 contraceptive patients per week, another quarter (28%) served 20–49 contraceptive patients per week, and the remaining 24% served 50 or more. This varied dramatically by service focus and provider type. Primary care–focused clinics served far fewer contraceptive clients per week than did reproductive health–focused clinics, and Planned Parenthood clinics served many more contraceptive clients per week than did any other provider type.

Scheduling

Overall, 52% of clinics reported that clients were offered an appointment time for an initial contraceptive visit on the same day they called or came in. The average wait time for an initial visit was just over three days. A somewhat greater share of primary care–focused clinics provided same-day appointments and shorter wait times, as compared with reproductive health–focused clinics, but there was little variation by Title X funding status in appointment availability. Compared with all other types of providers, Planned Parenthood clinics were most likely to have shorter wait times for an initial visit (1.2 days).

Four in 10 clinics (42%) reported offering some extended hours—either evenings (after 6P.M.), weekends or both. Again, the biggest variation in this measure was found when examining provider type. Every provider type was significantly different from all the others in terms of offering extended clinic hours. Health departments were least likely to offer extended hours (18%), followed by "other" clinics (29%) and FQHCs (57%). Planned Parenthood clinics were by far the most likely to offer extended clinic hours (78%). On average, clinics were open 39 hours per week; FQHCs reported the most hours open per week (45), and health departments reported the fewest (33).

Trends in clinic characteristics and logistics

As compared with data from 2010, data show that in 2015 clinics providing publicly funded family planning care were less likely to focus on reproductive health (50% vs. 44%; Table 1), were less likely to receive Title X funding (52% vs. 45%), and saw fewer contraceptive clients per week. For example, the proportion of clinics seeing fewer than 20 clients per week was 34% in 2010 and 47% in 2015. During the same period, clinics became more likely to offer same-day appointments (39% vs. 52%), and the average number of days to wait for an appointment declined by over two days (5.4 vs. 3.1 days).

On-Site Provision of Contraceptive and Other Health Services

On-site provision of a wide range of contraceptive methods is one of the hallmarks of the publicly funded clinic network. Contraceptive choice is critical to ensuring that women and couples adopt the best method for their current stage in life and lifestyle; women who are dissatisfied with their method are more likely to use it incorrectly or inconsistently.20 Recognizing the importance of contraceptive choice, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has identified as one of its Healthy People 2020 objectives the on-site provision by publicly funded family planning clinics of the full range of methods of contraception approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).21 In addition, recently released clinical recommendations for best practices in the provision of quality family planning services include offering patients a range of related preventive and screening services.22,23 It is important to monitor how successful publicly funded clinics are at providing these recommended services. Finally, with growing attention being paid by reproductive health care professionals to the issue of intimate partner violence (IPV),24 it is important to understand the role that clinics are currently playing with regard to IPV screening and the protocols and training available to staff.

In this section, we look at trends in the availability of different contraceptive methods and other types of health services in 2003, 2010 and 2015 and at patterns across types of clinics in 2015. Clinic administrators were asked if each method or service is: (1) provided or prescribed at this site; (2) not provided and clients are referred to another clinic or provider for the method or service; or (3) not provided nor referred. All figures presented in this section correspond to the percentages of clinics indicating that methods or services are provided or prescribed on-site. The percentages providing referrals can be found in Appendix A.

Trends in contraceptive method availability

On-site provision of the most widely used hormonal methods—oral contraceptives and injectables (e.g., Depo-Provera)—was high across all survey years; 95% or more of clinics provided each of these methods (Table 2). Provision of male condoms was nearly as high, with 90% or more of clinics providing this method in each survey year. Provision of most other methods rose significantly among clinics over the past decade: Most of the increase occurred between 2003 and 2010. Between 2010 and 2015, contraceptive method provision either rose slightly or stayed steady, depending on the method.

- On-site provision of the vaginal ring rose from 40% in 2003 to 81% in 2010 and to 86% in 2015; availability of the contraceptive patch rose from 75% in 2003 to 80% in 2010 and remained steady at 78% in 2015. Extended oral contraceptives (such as Seasonale), which were unavailable in 2003, were offered by 63% of clinics in 2010 and by 80% of clinics in 2015.

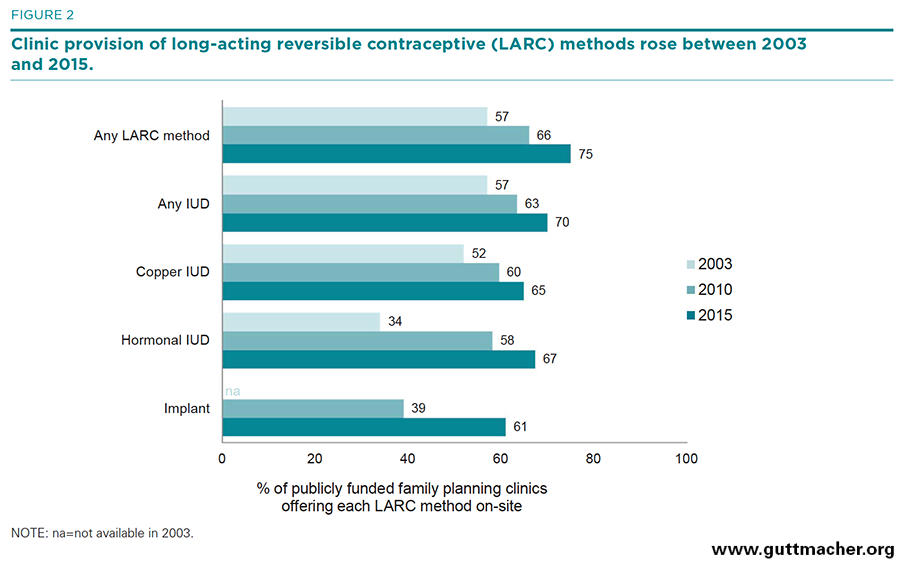

- Availability of long-acting methods rose significantly during the period. The implant, which was unavailable in 2003, was offered by 39% of clinics in 2010 and by 61% in 2015 (Figure 2). Provision of any type of IUD rose from 57% in 2003 to 63% in 2010 and to 70% in 2015, while availability of the copper IUD (e.g., ParaGard) rose from 52% to 60% to 65%, respectively, and availability of the hormonal IUD (e.g., Mirena) rose from 34% to 58% to 67%.

- Natural family planning instruction rose significantly between 2003 and 2010 (54% to 83%), while spermicide provision fell during that period (71% to 65%). The findings from the 2015 survey showed little change between 2010 and 2015 in the availability of either method (82% and 64%, respectively).

- On-site availability of emergency contraception at clinics stayed virtually the same between 2003 and 2010 (80–81%), and increased during the most recent period (85%).

- Provision of permanent contraceptive methods (tubal ligation, Essure and vasectomy) on-site at publicly funded family planning clinics, already quite low in 2003, fell even further in 2010 and stayed relatively unchanged in 2015: Provision of tubal sterilizations fell from 30% in 2003 to 14% in 2010 and to 12% in 2015, and provision of vasectomy in each respective year was 25%, 7% and 9%.

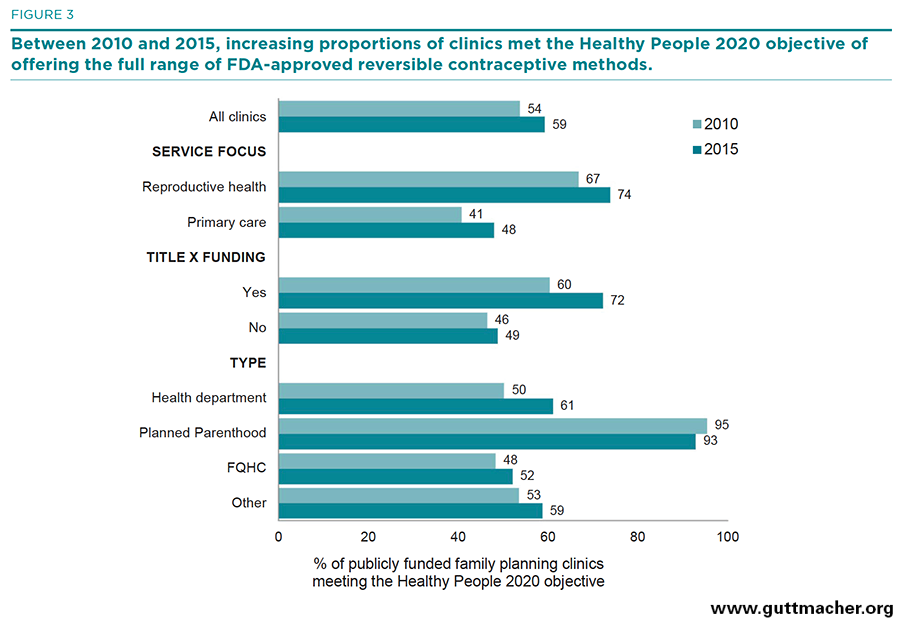

To summarize trends in the overall availability of reversible methods at publicly funded clinics, we looked at four different measures: the percentage of clinics offering a broad range of FDA-approved reversible methods (as defined in the Healthy People 2020 objective;21 Figure 3), the percentage of clinics offering any long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods (i.e., IUDs or implants), the mean number of reversible methods offered and the percentage of clinics offering at least 10 reversible methods.‡

- The proportion of clinics offering a broad range of FDA-approved reversible methods rose from 48% to 54% to 59%.

- The proportion of clinics offering any LARC method rose from 57% to 66% to 75%.

- The mean number of reversible methods offered by all clinics rose from 8.1 in 2003 to 9.2 in 2010 and to 11.2 in 2015.

- The proportion of clinics offering at least 10 reversible methods also rose over the same period, from 35% to 54% to 77%.

Variation in method availability

Service focus. In 2015, publicly funded clinics with a reproductive health service focus were significantly more likely than primary care–focused clinics to offer each reversible contraceptive method on-site. They provided an average of 12.1 different reversible methods, compared with 10.5 methods at primary care–focused clinics (Table 2). For some methods, the differences were striking, particularly with respect to LARC methods (IUDs were offered by 83% of reproductive health–focused clinics and 60% of primary care–focused clinics, and implants were offered by 74% and 51%, respectively), female barrier methods (referring to a range of methods, including the diaphragm and cervical cap, offered by 83% and 63%, respectively) and nonprescription methods (male condoms were offered by 97% and 91%, respectively, and natural family planning instruction or supplies by 91% and 75%). Overall, 74% of reproductive health–focused clinics met the Healthy People 2020 objective of offering a broad range of methods, compared with only 48% of primary care–focused sites (Figure 3).

Title X funding status. There was also a significant difference in on-site method provision between clinics according to Title X funding status in 2015. Title X–funded clinics were more likely to provide nearly all reversible methods on-site, except for extended-regimen oral contraceptives and the patch, than were non-Title X–funded clinics. Overall, the average number of methods provided on-site by Title X–funded clinics (12.0) was significantly greater than the number provided by clinics not receiving Title X funding (10.5).

Provider type. For every reversible method, there were wide and significant differences in on-site method provision among clinics according to provider type. With very few exceptions, Planned Parenthood clinics were significantly more likely than all other types of clinics to provide most methods on-site. Ninety-nine percent of Planned Parenthoods provided at least 10 reversible methods on-site, compared with 71–81% of all other provider types. Planned Parenthood clinics were also more likely than all other types of clinics to provide a LARC method (98% vs. 69–77%), and were much more likely to have met the Healthy People 2020 objective to provide the full range of all FDA-approved methods (93% vs. 52–61%).

Medicaid expansions. Clinics in states with a Medicaid expansion were more likely than clinics in other states to report having met the Healthy People 2020 objective through on-site provision of a broad range of FDA-approved contraceptive methods (61% vs. 51%), and they were more likely to report on-site provision of any LARC method (77% vs. 67%). On average, clinics in expansion states offered a greater number of contraceptive methods (11.3 methods vs. 10.5; data not shown).

Difficulties providing methods. Four in 10 clinics (42%) reported that they did not stock certain methods because of cost. This represents a significant decrease from the 57% of clinics reporting this situation in 2010. The most common methods not stocked due to their cost include IUDs, the implant and the patch. Health departments were the most likely to report not stocking certain methods because of cost (49%) and FQHCs were the least likely (37%). Moreover, fewer clinics in Medicaid expansion states reported that they were unable to stock certain methods due to cost, compared with clinics located in non-expansion states (38% vs. 59%).

Provision of other health services

All clinics that provide publicly funded contraceptive care also provide at least some general preventive and screening services and other related sexual and reproductive health services; many clinics provide a wide range of such services (Table 3). In 2015, we asked about the provision of a much broader range of services than in 2010; we therefore report trends only for those services that were asked about in both surveys and for which significant differences exist across the survey years.

Primary care. In 2015, 63% of all publicly funded family planning clinics reported providing primary care, an increase from 52% in 2010. Primary care provision varied widely among clinics: Only 25% of reproductive health–focused clinics and just over a third of Title X–funded clinics provided primary care. FQHCs were most likely to provide primary care (96%), while Planned Parenthood sites were least likely (13%).

Pregnancy testing. Virtually all (99%) publicly funded family planning clinics, regardless of service focus, funding or type, reported providing pregnancy testing.

STI services. The vast majority of clinics reported providing STI services, with only small variation between 2010 and 2015: Ninety-eight percent provided testing or screening for chlamydia or gonorrhea, and 94% provided these services for syphilis (a decrease from 97% in 2010). Ninety-seven percent provided STI treatment and 79% provided expedited therapy for the client’s partner at the same visit. Reproductive health–focused clinics were more likely than primary care–focused clinics to offer some STI services.

HIV testing. Ninety-four percent of clinics provided HIV testing, but only about one-third (37%) offered pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV (PrEP). While reproductive health–focused clinics were more likely to offer testing (96% vs. 93%), primary care–focused sites were more likely to offer PrEP (48% vs. 22%).

HPV vaccination. Ninety percent of clinics reported providing the HPV vaccination on-site in 2015, an increase from 87% in 2010. Primary care–focused clinics were more likely to do so than reproductive health–focused sites (93% vs. 87%).

Cervical cancer screening. Nearly all clinics (95%) screened for cervical cancer using conventional or liquid-based Pap tests. Higher proportions of reproductive health–focused or Title X–funded clinics, compared with primary care–focused or non-Title X clinics, offered this method. In addition, 70% of clinics offered combined Pap and DNA testing, an increase from 44% in 2010. Availability of this screening method did not vary according to service focus or Title X funding status. Just over one-third (37%) of clinics reported providing colposcopy services on-site. Planned Parenthood clinics, FQHCs and sites in the "other clinics" category were all much more likely than health departments to provide colposcopy (57%, 43% and 44%, respectively, vs. 19%).

Breast cancer screening. Virtually all clinics (97%) provided clinical breast exams on-site, but only two in 10 (20%) were equipped to provide mammography services. Clinics focused on primary care were more likely to offer mammography (25%) than were reproductive health–focused clinics (15%).

Hepatitis-related services. The majority of clinics reported providing hepatitis B vaccinations (81%) and screening for hepatitis C (77%); about a third (29%) reported offering hepatitis C treatment. Primary care–focused clinics were more likely to provide all three services (91%, 86% and 43%, respectively), compared with reproductive health–focused clinics (68%, 67% and 11%), and there was wide variation across clinic types.

Preconception care. More than eight in 10 clinics (87%) reported providing preconception counseling to their clients, and three-quarters (73%) provided folic acid supplements. Reproductive health–focused clinics, Title X–funded clinics, health departments and Planned Parenthood sites were more likely than other categories of clinics to offer preconception counseling; folic acid supplement availability was greater at primary care–focused clinics and FQHCs.

Prenatal care. Fewer than half (41%) of publicly funded family planning clinics reported providing prenatal care services. Reproductive health–focused sites, Title X–funded clinics, Planned Parenthood clinics and health departments were significantly less likely than the other types of clinics to provide prenatal care.

Infertility-related services. About half of clinics reported providing infertility counseling (49%), an increase from 42% in 2010. Over half (55%) offered infertility testing in 2015, a service that was not included on the 2010 survey. Reproductive health–focused clinics were more likely than primary care–focused clinics to provide counseling for infertility (57% vs. 42%), while the opposite was true for infertility testing (50% vs. 59%).

Abortion services. Few publicly funded family planning clinics reported providing abortion services (8% provided medication abortion and 4% provide surgical abortion); those providing abortion services used private sources of funding to pay for them. (Title X funds cannot be used for abortion, and abortion activities must be separate and distinct from Title X project activities.)

Breast-feeding counseling and support. Two-thirds (62%) of clinics provided breast-feeding counseling and support. Primary care–focused clinics were more likely to do so than were reproductive health–focused clinics (65% vs. 58%). There was significant variation in provision of breast-feeding support across the clinic types, and health department sites were more likely than all other types to provide this service.

Other screening services. Nearly all publicly funded family planning clinics reported providing body mass index screening (96%) and screening for alcohol, tobacco or other drug use (93%). These services were nearly universal at primary care–focused clinics (98%) and slightly less common (88–92%) at reproductive health–focused sites. Seventy-nine percent of clinics reported providing diabetes screening, up from 72% in 2010, and 69% reported offering mental health screening services, up from 64% in 2010. Again, primary care–focused clinics, particularly FQHCs, were more likely to offer such services than were reproductive health–focused clinics.

Vaccinations not related to reproductive health. Seventy-nine percent of clinics reported providing vaccines not related to reproductive health. The majority of health departments (89%), FQHCs (88%) and "other" clinics (65%) reported doing so, compared with only one-fifth (21%) of Planned Parenthood clinics.

Addressing intimate partner violence at the clinic

- Eight in 10 clinics (84%; Table 4) reported screening their clients for intimate partner violence (IPV; no change from 83% in 2010; data not shown), and one-third (37%) offered some kind of intervention services for clients who reported experiencing IPV. While primary care–focused clinics were less likely than reproductive health–focused clinics to screen clients for IPV, they were more like to offer intervention services; health departments were less likely to provide intervention services than were Planned Parenthood clinics, FQHCs and "other" clinics.

- Seventy-seven percent of clinics reported having protocols or polices in place to guide their IPV screening or intervention services, and 64% of clinics provided for staff training on IPV screening, intervention or state policies. Reproductive health–focused clinics, particularly Planned Parenthood sites, were most likely to provide such services.

Clinical Practices to Facilitate Access to and Continuation of Method Use

Family planning providers follow a variety of practices and protocols that may help to facilitate initiation and continuation of clients’ chosen method of contraception. Practices that require women to visit more than one place or wait before starting a method may impede successful initiation of a method. Clinic administrators were asked a variety of questions to assess the typical practices around method initiation and dispensing of oral contraceptives and LARC methods at their site and online. In this section, we examine clinic practices in 2015 and changes since 2010, where possible.

Oral contraceptive dispensing protocols

Successful initiation of oral contraceptive use may be improved by use of the "quick-start" protocol (beginning pill use on the day of the visit, regardless of where the client is in her menstrual cycle),25 by allowing new oral contraceptive clients to delay the pelvic exam until a later visit,26–28 and by providing clients with a large supply of pills at the initial visit.29 Streamlined dispensing protocols that require only one visit reduce barriers to receiving a method and help to ensure that clients start on their method right away.

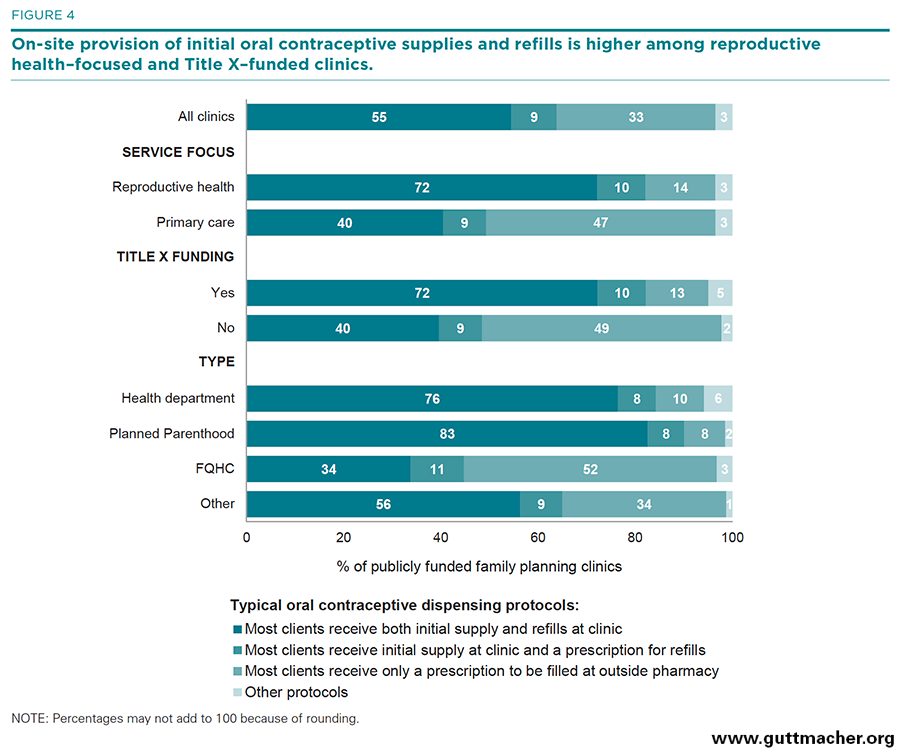

On several measures, more clinics in 2015 than in 2010 followed oral contraceptive dispensing protocols that allowed initial users to obtain their method faster and more easily; however, a growing minority of clinics reported that neither the initial oral contraceptive supplies nor refills were available on-site and that all clients received a prescription to fill at an outside pharmacy. In the next two sections, we present figures that compare the results for specific dispensing protocols individually across clinics, according to service focus, Title X funding and type.

Pills supplied on-site. Half of clinics (55%) reported providing most oral contraceptive users with both initial pill supplies and refill supplies on-site (Table 5, and Figure 4), a decrease from 63% in 2010. Reproductive health–focused clinics were more likely than primary care–focused sites to provide pill supplies on-site (72% vs. 40%), and Title X–funded clinics were more likely than clinics not receiving such funding to do so (72% vs. 40%). Health department and Planned Parenthood clinics were more likely than FQHCs and "other" clinics to provide pill supplies on-site (76–83% vs. 34–56%).

Pills refilled through prescription. Few clinics (9%) provided most users with an initial supply on-site and a prescription for refill supplies to be filled at a pharmacy. This percentage remained unchanged from 2010, and there was little variation across clinic types.

All pills supplied through prescription. One-third (33%) of clinics provided clients with a prescription that needed to be filled at an outside pharmacy; this represents a significant increase from the 24% that did so in 2010. Reproductive health–focused clinics were less likely than primary care–focused sites (14% vs. 47%), and Title X–funded clinics were less likely than clinics not receiving such funding (13% vs. 49%), to provide a prescription without offering the method on-site. Health department and Planned Parenthood clinics were less likely than FQHCs and "other" clinics to do so (8–10% vs. 34–52%).

Pills supplied at first visit. Nearly two-thirds (64%) of clinics reported providing fewer than six months’ pill supply at an initial visit, typically providing a three-month supply. More than one-third (36%) of clinics reported providing at least a six-month supply, typically a full year’s supply; this represents an increase from 28% in 2010. Planned Parenthood clinics were more likely than all other provider types to offer at least a six-month pill supply (69%), while health department clinics were the provider type least likely to do so (23%).

Pills supplied at follow-up visit. At a follow-up visit for pill supplies, the majority of clinics provided at least a six-month supply (71%). There was less variation in provision according to provider type.

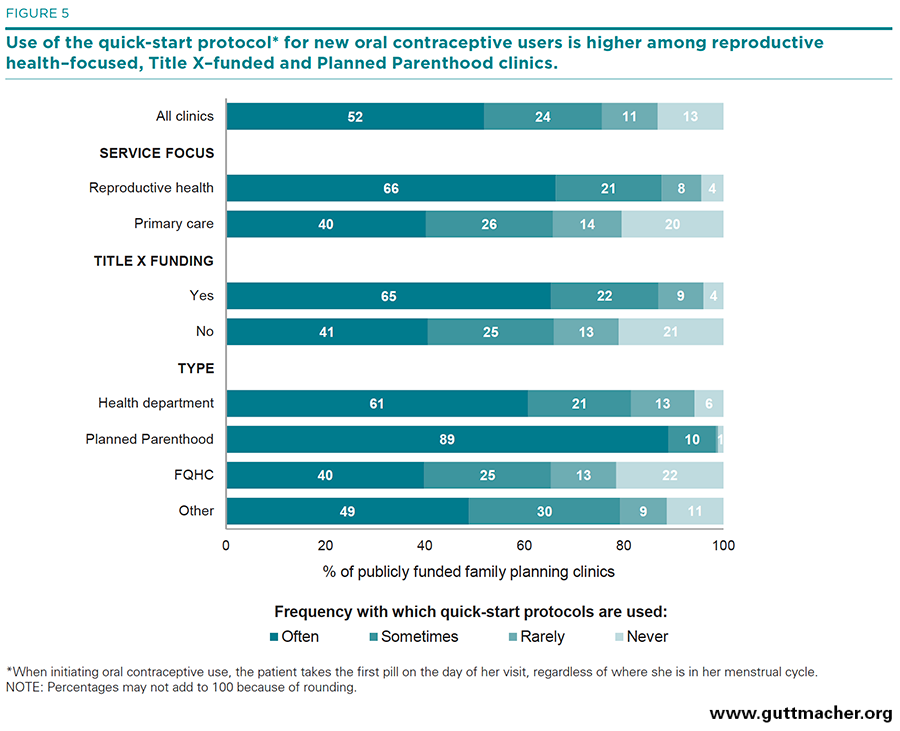

Quick start. Overall, three-quarters of clinics (76%) reported using the quick-start protocol often or sometimes, an increase from 66% in 2010. Reproductive health–focused sites and Title X–funded sites were more likely than primary care–focused or non-Title–X funded sites to use this protocol (88% vs. 66%, and 87% vs. 66%, respectively; Table 5, and Figure 5). Planned Parenthood clinics were more likely than all other provider types to use the quick-start protocol often or sometimes (99%), and FQHCs were less likely than all other provider types to do so (65%).

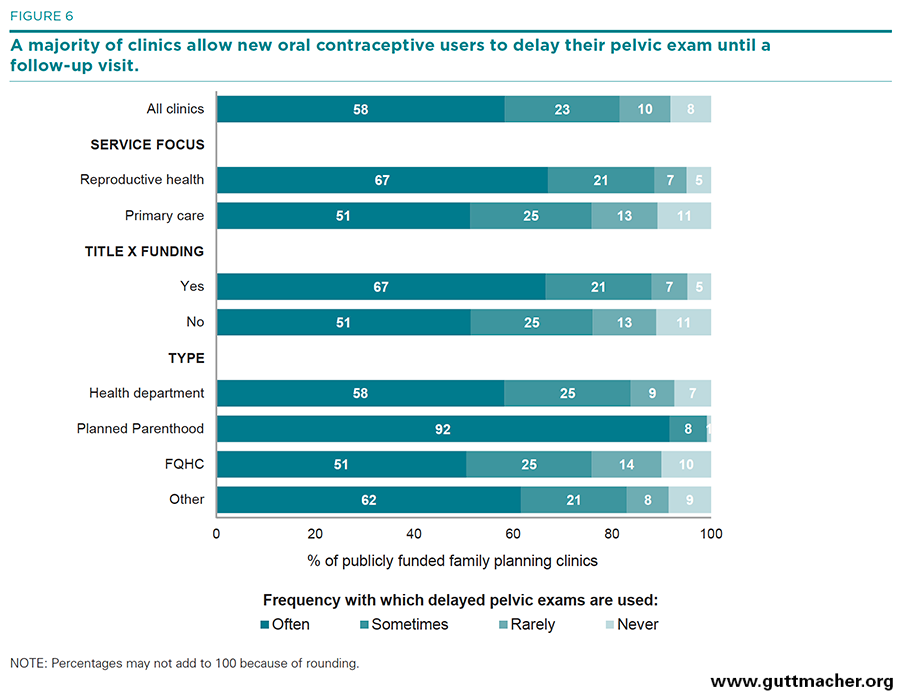

Delayed pelvic exam. Eight in 10 (81%) clinics reported allowing new oral contraceptive clients to delay the pelvic exam often or sometimes, an increase from 66% in 2010 (Figure 6). The pattern of clinics reporting this policy—by service focus, Title X funding status and provider type—is similar to that of clinics using the quick-start protocol.

Advance provision of emergency contraception. Among all clinics, 42% reported often or sometimes dispensing or prescribing emergency contraceptive pills ahead of time for a client to keep at home; the same proportion reported this practice in 2010. Reproductive health–focused clinics and Title X–funded clinics were more likely than primary care–focused or non-Title–X funded sites to do this (53% vs. 32%, and 50% vs. 35%, respectively). Planned Parenthood clinics were much more likely to offer advance provision than were other provider types (89% vs. 34–48%).

Telemedicine. A new practice of prescribing oral contraceptives over the phone or Internet without a clinic visit has emerged and may be especially useful for women living in rural areas. In 2015, only 15% of clinics reported often or sometimes offering telemedicine prescriptions for oral contraceptives. FQHCs were more likely than either health departments or Planned Parenthoods to have adopted this approach (20% vs. 6% and 9%, respectively).

Injectable and LARC dispensing protocols

Protocols that ensure clients can obtain their chosen method, including LARCs, in one visit reduce barriers to method initiation. And current standards of care suggest LARC use is appropriate for all ages and parities, although LARC methods have historically been recommended primarily for adult women and women with children, causing lingering barriers for adolescents and nulliparous women who might otherwise choose LARC methods. In this section, we look at the dispensing protocols for injectable and LARC methods among publicly funded clinics.

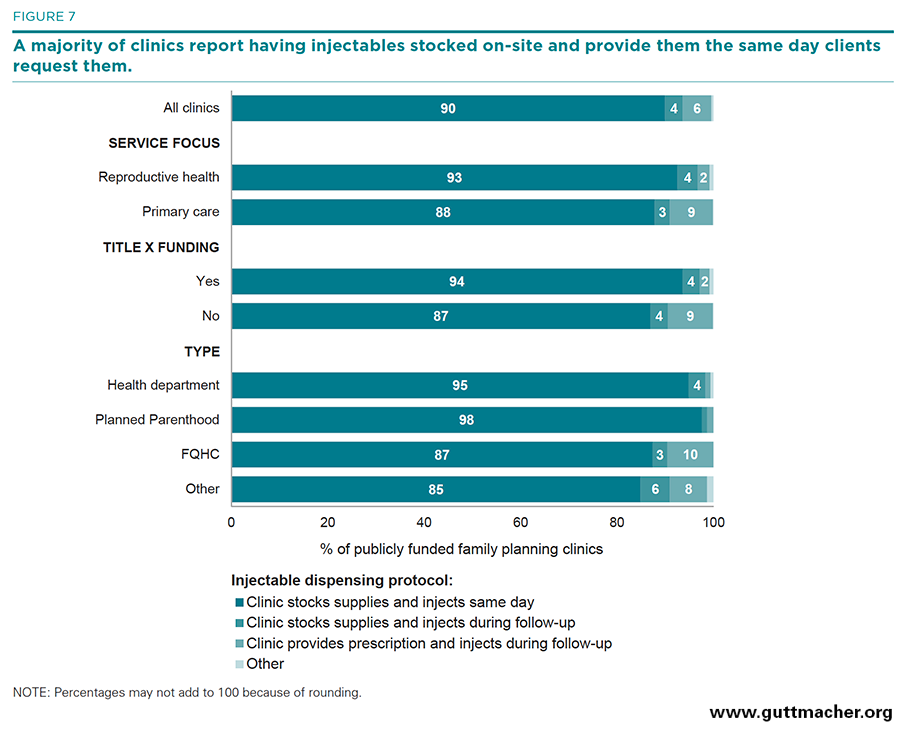

Injectables. When dispensing injectable hormonal contraception (e.g., Depo-Provera), the vast majority of clinics (90%) had the method stocked on-site and provided it to the client during the same visit it was requested (Table 6 and Figure 7). However, 4% of clinics reported that clients had to request the method and then return to the clinic for the injection. Virtually all health department and Planned Parenthood clinics reported offering injectables in one visit (95–98%), compared with 85–87% of FQHCs and "other" clinics. Non–Title X clinics were more likely than Title X clinics to require clients to obtain their method from outside of the clinic and return for the injection (9% vs. 2%), and FQHCs and "other" clinics were more likely than health department and Planned Parenthood clinics to do so (8–10% vs. 1%; data not shown).

IUDs. Among clinics that provided the IUD, nearly all clinics (96%) reported purchasing IUD supplies and performing insertions on-site, up from 85% of clinics in 2010 (data not shown). Specifically, 41% reported performing insertions during the same appointment the method was requested, and 55% reported requiring a follow-up appointment for insertion. Reproductive health clinics were more likely than primary care–focused clinics to offer same-day insertion (49% vs. 32%), Title X–funded clinics were more likely than non–Title X clinics to do so (46% vs. 36%) and Planned Parenthood clinics were more likely than other types of clinics to do so (81% vs. 30–48%).

Implants. Among clinics that provided the implant, 51% reported stocking implant supplies in advance and providing insertions on-site during the same appointment the method was requested. Health department clinics, FQHCs and "other" clinics were less likely to report this practice (43–54%) than were Planned Parenthoods (83%).

LARC methods. The majority of clinics provided hormonal or copper IUDs or implants to teens and young adults (68%) and to women who had not yet had children (64%), two groups that have historically had difficulty obtaining these methods. Compared with primary care clinics, reproductive health–focused clinics were more likely to offer LARC methods to these groups (75–83% vs. 54–56%); nearly all Planned Parenthood clinics (95–97%) offered LARC methods to teens and nulliparous women. Only one-quarter of clinics (25%) offered the copper IUD as a method of emergency contraception. Planned Parenthood clinics (65%) were much more likely to offer the IUD for this purpose, compared with all other types of clinics (14–26%).

Variation in key method availability and dispensing indicators by clinic characteristics

The data presented so far with regard to on-site method availability and use of protocols to facilitate initiation and continuation of methods indicate clear patterns that distinguish different types of clinics. Figures 8–10 highlight those differences for each of the three clinic characteristics examined.

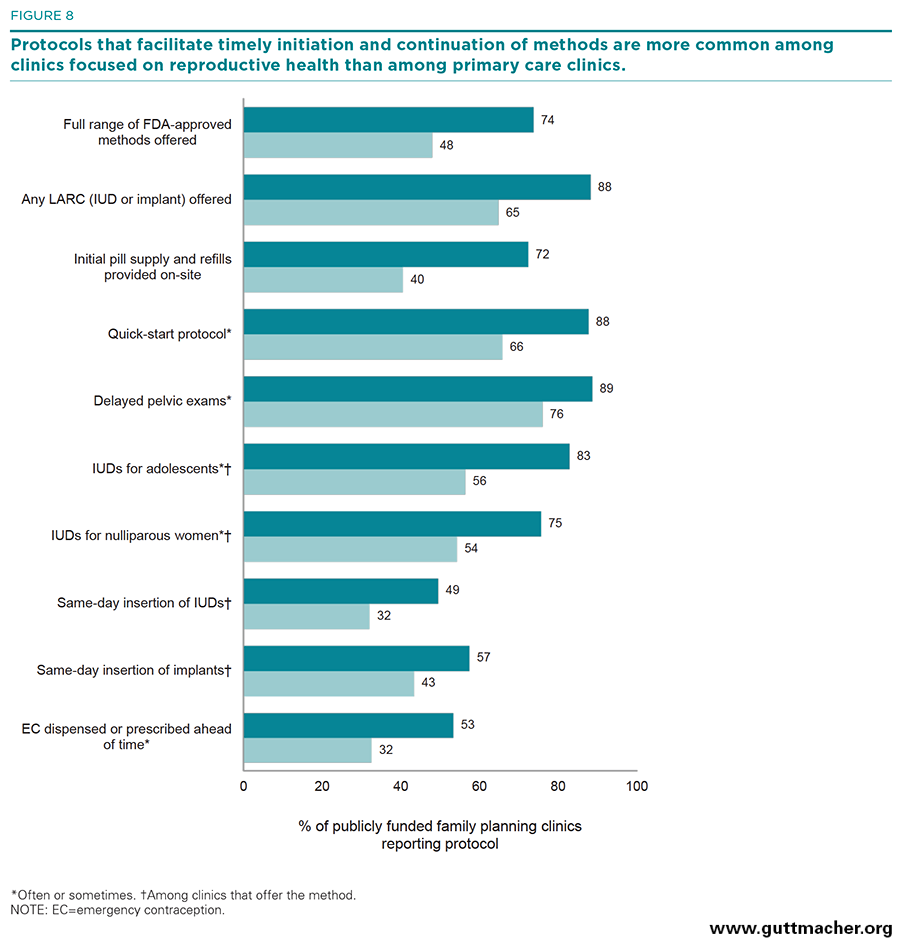

Service focus. Compared with primary care–focused clinics, clinics that specialized in the provision of reproductive health care were significantly more likely to have dispensing protocols that facilitate initiation and continuation of oral contraceptives and LARC methods. Reproductive health–focused clinics were more likely to provide initial oral contraceptive supplies and refills on-site (72% vs. 40%), to provide initial oral contraceptives using the quick-start protocol (88% v. 66%), to allow women to delay their pelvic exam when initiating hormonal contraceptives (89% vs. 76%), to provide LARC methods to adolescents or nulliparous women (75–83% vs. 54–56%), and to offer same-day insertion of LARC methods (49–57% vs. 32–43%; Figure 8).

Funding status. Similarly, Title X–funded clinics did much better on key indicators measuring clinics’ use of protocols designed to facilitate method initiation and continuation, as compared with sites not funded by Title X. Title X–funded clinics were more likely to provide initial oral contraceptive supplies and refills on-site (72% vs. 40%), to use the quick-start protocol for oral contraceptive initiation (87% vs. 66%), to allow women to delay the pelvic exam when initiating a hormonal contraceptive method (88% vs. 76%), to provide LARC methods to adolescents or nulliparous women (75–80% vs. 54–58%), and to offer same-day provision of LARC methods (46–54% vs. 36–47%; Figure 9).

Clinic type. When comparing the different types of publicly funded family planning clinics on these key dispensing indicators, we found wide variation in the proportions implementing protocols aimed at facilitating method initiation and continuation. Overall, Planned Parenthood clinics did significantly better than all other clinic types on these measures. Eight in 10 (83%) Planned Parenthood clinics provided initial oral contraceptive supplies and refills on-site, followed closely by health departments (76%); in comparison, only 34–56% of FQHCs and "other" clinics did so. Nearly all Planned Parenthood clinics (99%) used quick-start or delayed pelvic protocols, compared with 65–84% for all other clinic types. Similarly, 95–97% of Planned Parenthood clinics provided LARC methods to adolescents or nulliparous women, compared with 55–71% for all other clinic types; 81–83% of Planned Parenthood clinics offered same-day insertion of LARC methods, compared with 30–54% of all other clinic types (Figure 10).

Dispensing protocols by Title X funding status and clinic service focus or type

As reported above, clinics that received Title X funding were more likely to implement service delivery practices that facilitate initiation and continuation of contraceptive methods. This pattern persists within subgroups of clinics by service focus and type and suggests that receipt of Title X funding, along with the oversight and guidance provided to clinics that are part of this network, offers an added benefit to these sites and improves quality of care for their clients.

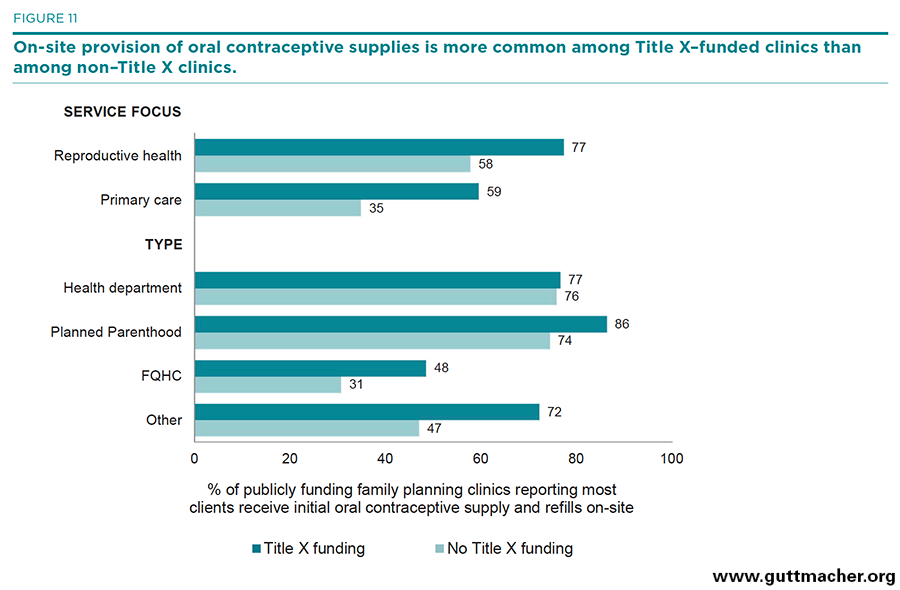

- Reproductive health–focused clinics that received Title X funding were the most likely to provide oral contraceptive supplies and refills on-site, and they were significantly more likely to do so than were reproductive health–focused clinics that do not get Title X funding (77% vs. 58%; Figure 11). And, although primary care–focused clinics overall were less likely to provide oral contraceptives on-site, those that received Title X funds were much more likely to do so than were primary care–focused clinics with no Title X funding (59% vs. 35%). High proportions of both health department and Planned Parenthood clinics provided oral contraceptive supplies and refills on-site, and there was little variation by Title X funding status. However, among FQHCs and "other" clinics, there was wide variation according to Title X funding status, with those receiving Title X funding more likely to implement these protocols (48% vs. 31% for FQHCs and 72% vs. 47% for "other" clinics).

- Similar patterns were found for clinics’ use of the quick-start protocol for initiating contraceptive pill use: Clinics that received Title X funding were more likely than those without such funding to use this protocol often or sometimes, and this pattern was especially pronounced among primary care–focused clinics (81% vs. 61%) and among FQHCs (85% vs. 61%) and "other" clinics (93% vs. 71%; Figure 12).

Services offered online

Clinics increasingly offer online services, from appointment scheduling to obtaining prescriptions to communicating with physicians and other medical staff. These practices improve client experience because they reduce wait times on the phone and in some cases eliminate the need to travel to a clinic. In this section, we asked providers about a range of online services.

- Only 18% of publicly funded family planning clinics reported that clients often or sometimes schedule their appointments online (Table 7). Planned Parenthood sites were significantly more likely than other types of clinics to report implementation of an online scheduling system (74% vs. 3–20%).

- Overall, very few clinics reported that clients often or sometimes obtained an initial prescription for a contraceptive method online (3%), although FQHCs reported this more often than other types of clinics (5% vs. 0–2%). One-fifth (21%) of clinics, however, reported that clients used online services to order refills for prescription methods. Planned Parenthood clinics and FQHCs were most likely to report that clients used this service (25–32% vs. 4–19% for health departments and "other" clinics).

- One-quarter (24%) of clinics reported that clients often or sometimes asked staff medical or follow-up questions online. FQHCs were most likely (34%), and health departments were least likely (10%), to report that this took place.

Community Linkages

Publicly funded family planning clinics are one component of a much larger system of health care providers. For many women and men, family planning clinics provide an entry point into the larger health care system. This may be especially true for relatively healthy young women, whose need for contraception may motivate them to make a health care visit that they might otherwise forgo or deem unnecessary. To better understand whether clinics are indeed providing their clients with needed referrals and to explore how publicly funded family planning providers are connected with the broader health provider system, we asked clinics whether specific types of providers available in their community referred clients formally or informally to the clinic or vice versa. The specific types of providers with which a clinic may have a referral relationship included: FQHCs, other community clinics providing primary care, school-based health centers, STI clinics, private obstetrician-gynecologist offices, other private physician or group practices, social service agencies (e.g., those administering benefit programs such as WIC, SNAP and TANF) and home visiting programs.

Referrals from other providers

Any agreements. Nearly all clinics (94%) reported that one or more providers in the community regularly referred their clients to the clinic (Table 8). Nine in 10 (93%) reported regularly receiving referrals from at least one publicly funded provider that offered primary or general care or other medical services, and 75% reported regularly receiving referrals from at least one private provider, such as an obstetrician or gynecologist, or other physician or group practice. Reproductive health–focused clinics and Title X–funded clinics were particularly likely to maintain such relationships. While there was no difference across the types of clinics that received referrals from public clinics, health departments and Planned Parenthoods were more likely to receive referrals from private providers than were FQHCs and "other" clinics (81–92% vs. 69–73%). When asked which reproductive health services clients were most likely to be referred to them for, clinics most commonly reported contraceptive services, including provision of LARC methods (data not shown). A smaller share of clinics reported receiving referrals for STI testing and treatment, as well as gynecological and breast exams.

Formal agreements. It was relatively uncommon for clinics to report a formal relationship where another provider, agency or program referred clients to the clinic (12–24%). Title X clinics were less likely to report this type of relationship with private physicians than were clinics that did not receive funding (9–11% vs. 15–18%), and Planned Parenthood clinics were also generally less likely to report this type of relationship with both public and private providers than were the other clinic types (1–8% vs. 8–26%).

Informal agreements. In comparison, between one-third and one-half of clinics (39–59%) regularly maintained an informal referral relationship where another provider referred clients to the clinic. Reproductive health–focused clinics were more likely to maintain such relationships with both public and private providers, compared with primary care–focused clinics (44–70% vs. 34–50%), as were clinics that received Title X funding, compared with those that did not (45–68% vs. 34–51%). Planned Parenthood clinics were also more likely than the other types of clinics to maintain informal relationships with public providers (47–86% vs. 34–67%) and with private providers (82–83% vs. 37–69%).

Referrals to other providers

Any agreements. Nearly all clinics (97%) reported that they regularly referred some clients to one or more providers in their community (Table 9). Ninety-five percent of clinics reported referring some clients to other public providers in their community, and 85% reported referring some clients to private providers. Again, reproductive health–focused clinics and clinics receiving Title X funding were more likely to refer clients to other providers in the community. While there was not much variation across the types of clinics that referred to public providers, health departments and Planned Parenthoods were more likely to refer their clients to private providers than were FQHCs and "other" clinics (94% vs. 80%).

Formal agreements. Fewer than one-third of clinics reported formal relationships for referring clients to other public (8–28%) or private (25–32%) providers. Primary care–focused clinics were more likely to formally refer clients to private providers than were reproductive health–focused clinics (32–40% vs. 17–21%), as were clinics that did not receive Title X funding, compared with those that did (29–37% vs. 21–25%). Planned Parenthoods were less likely than other clinic types to formally refer clients to public providers (2–9% vs. 7–35%), and FQHCs were more likely than other clinic types to formally refer to private providers (34–42% vs. 9–27%).

Informal agreements. Again, informal referral relationships were more common than formal ones. Between one-quarter and one-half of clinics (26–57%) regularly maintained an informal referral relationship where the clinic referred clients out to another provider. Reproductive health–focused clinics were generally more likely than primary care–focused clinics to maintain such relationships with public providers (34–69% vs. 19–52%) and with private providers (65–67% vs. 35–38%). Likewise, clinics that received Title X funding were more likely than those that did not to maintain such relationships with public providers (32–64% vs. 21–53%) and with private providers (61–62% vs. 38–42%). Planned Parenthood clinics were generally more likely than other types of clinics to maintain informal relationships with public providers (42–85% vs. 16–65%) and with private providers (75–79% vs. 31–66%).

Affordability of Care

Publicly funded family planning clinics, like other safety-net providers, take steps to ensure that clients have easy access to services they can afford. Ensuring affordable care is one of the most important aspects of clinic accessibility. Providing free or reduced-fee services, on the basis of clients’ income, is one way that many clinics serve poor and low-income individuals. One important way of making care affordable is by participating in the Medicaid health plans that serve low-income women in their communities. Participating in both public and private health plans has become even more important in recent years, as more women gain insurance under provisions of the Affordable Care Act.

Insurance coverage

Clinic administrators were asked to provide information about the percentage of contraceptive visits in 2014 that were made by clients who had some form of insurance, regardless of whether or not the clinic billed that insurance for the visit.§ Response categories included four types of third-party reimbursement: full-benefit Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Medicaid family planning–specific expansion program, other public insurance and private insurance. The survey also asked about the percentage of visits that were made by clients who had neither public nor private insurance coverage.

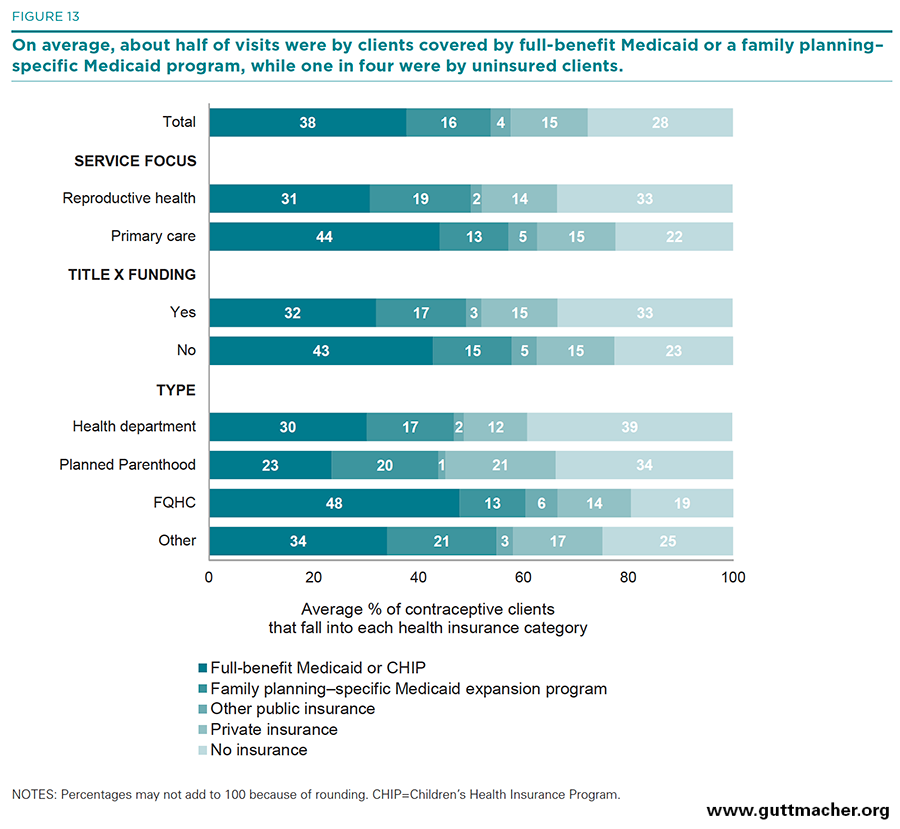

- Clinics reported that nearly six in 10 contraceptive visits, on average, were made by clients with public coverage, either full-benefit Medicaid (38%), a Medicaid family planning–specific expansion program (16%), or some other public health insurance (4%; Table 10, and Figure 13). Fifteen percent of visits were made by clients with private health insurance and 28% by clients with no health insurance coverage.

- On average, the proportion of contraceptive visits made by clients with no insurance was higher at reproductive health–focused clinics than at primary care–focused clinics (33% vs. 22%) and at Title X–funded clinics than at clinics not receiving Title X funds (33% vs. 23%). Among the four clinic types, a higher proportion of clients without insurance visited Planned Parenthood clinics and health departments than FQHCs and "other" clinics (34–39% vs. 19–25%).

- Compared with reproductive health–focused clinics, a higher proportion of visits to primary care–focused clinics were made by clients with full-benefit Medicaid coverage (44% vs. 31%); the proportions were similar for Title X–funded clinics compared with clinics that did not receive Title X funding (43% vs. 32%). Compared with the other three provider types, a higher proportion of contraceptive visits at FQHCs were made by clients with full-benefit Medicaid (48% vs. 23–34%).

- A higher proportion of visits at Planned Parenthood clinics than at health departments or FQHCs were made by women with private coverage (21% vs. 12–14%).

- Not surprisingly, clinics in Medicaid expansion states reported that, on average, higher proportions of contraceptive visits were made by clients covered by full-benefit Medicaid or a family planning–specific Medicaid program (40% and 18%, respectively), compared with visits to clinics located in non-expansion states (27% and 6%). As a result, a higher proportion of visits in non-expansion states than in expansion states were among clients with no health insurance coverage (43% vs. 24%).

Contracting with health insurance plans

- In 2015, more than eight in 10 clinics (84%) reported having one or more contracts with health plans—either with Medicaid or with private health insurers—up from just over half of clinics (53%) in 2010 (Table 11).

- Overall, 80% of clinics reported having one or more contracts with Medicaid health plans, up from 40% in 2010; 73% reported having health plan contracts with private insurers, up from 33% in 2010 (Figures 14 and 15).

- There was little variation by service focus or Title X funding in the overall proportions of clinics with contracts of any type, or contracts with Medicaid plans. However, reproductive health–focused clinics and Title X–funded clinics were less likely than primary care–focused and non–Title X clinics to have contracts with private insurers.

- Planned Parenthood clinics were more likely than all other types of clinics to have one or more health plan contracts (98% vs. 73–91%) or one or more contracts with private insurers (95% vs. 54–84%).

- Health departments were the clinics least likely to have a health plan contract (27% had no contracts, compared with 2–19% of all other types of providers). Sixty-nine percent of health departments reported contracts with Medicaid plans, and only 54% reported contracts with private plans—significantly lower proportions than among all other clinic types.

Discussion

Publicly funded family planning clinics are a vital component of the health care safety net, offering millions of women a source for affordable health care. In addition to providing contraceptive services, clinics also offer a wide range of related reproductive health services. Many provide general preventive care and screening services, and some provide comprehensive primary care. In 2015, we asked a nationally representative sample of these clinics to respond to questions about their services and service delivery practices and protocols, and we compared this information with similar information collected in 2010. We found that over this period, more and more clinics began providing specific reproductive health and non–reproductive health services. However, there was wide variation among types of clinics in service provision, practices and protocols. Below we highlight key changes over time and differences in service provision between types of clinics.

Progress on Healthy People 2020 objectives

The proportion of clinics providing a wide range of contraceptive methods on-site was higher in 2015 than in 2010. Specifically, nearly six in 10 clinics (59%) met the Healthy People 2020 objective (FP-3.1) of offering the full range of FDA-approved methods, compared with 54% in 2010. This indicates positive progress toward meeting the Healthy People 2020 target of 67% of publicly funded clinics offering the full range of methods. Among Title X–funded clinics, the proportion of sites offering the full range of methods rose from 60% to 72%, already surpassing the Healthy People 2020 target. A second, related Healthy People 2020 objective (FP-3.2) is to increase the proportion of publicly funded family planning clinics that offer emergency contraception on-site. Our findings show that between 2010 and 2015, this indicator also rose, from 81% to 85% and is well on its way to meeting the 2020 target of 88%.

Increased provision of noncontraceptive care

In addition to increasing method provision, publicly funded family planning clinics also increased their provision of many vital noncontraceptive services. Provision of primary care services rose from 52% of clinics in 2010 to 63% in 2015, provision of diabetes screening increased from 72% to 79%, and provision of mental health screening from 64% to 69%. In addition, most clinics in 2015 provided screening for body mass index (96%) or substance use (93%); these data are not available for 2010. And although most Title X–funded clinics did not report providing primary care services, the proportion doing so rose from 29% to 38% between 2010 and 2015.

Increased provision of LARC methods

One of the most significant changes in the contraceptive landscape over the past decade has been the development and marketing of new LARC methods, including hormonal intrauterine systems and the single-rod implant. Intrauterine methods, originally considered appropriate only for older women who had already had children, are now recommended as a first-line method for women of all ages and parities, including adolescents and nulliparous women.30 As a result, increasing numbers of women and teens rely on LARC methods,31 a trend that may have contributed to recent declines in unintended pregnancy and abortion.32 Publicly funded family planning clinics—a high proportion of which offer LARC methods—have been at the forefront of these developments. In 2015, three in four clinics offered at least one LARC method on-site compared with two-thirds of clinics in 2010. Seventy percent of clinics offer at least one intrauterine method, and 61% offer the implant—up from 63% and 39%, respectively, in 2010. Provision of any LARC method in 2015 varied widely by service focus and funding: Reproductive health–focused sites were much more likely to offer one of these methods than were primary care–focused clinics (88% vs. 65%) and Title X–funded sites were more likely to do so than clinics not funded by Title X (85% vs. 67%). Virtually all Planned Parenthood clinics offered at least one LARC method (98%), compared with 69–77% of other clinic types.

Strong performance of Title X clinics on key indicators

In addition to making a range of methods, including LARCs, available on-site, publicly funded family planning clinics often implement a variety of practices and protocols that help to facilitate women’s uptake and continuation of contraceptive methods. In particular, Title X–funded clinics have been especially proactive in adopting best practices for the delivery of quality family planning care, using Title X program standards as a guide. As a result, Title X–funded clinics in 2015 did much better than those not funded by Title X on key indicators: provision of initial supply of oral contraceptives and refills on-site (72% vs. 40%), implementation of the quick-start protocol for oral contraceptive initiation (87% vs. 66%), allowing women to delay their pelvic exam when initiating a hormonal contraceptive method (88% vs. 76%), provision of LARC methods to adolescents or nulliparous women (75–80% vs. 54–58%), and same-day provision of LARC methods (46–54% vs. 36–47%).

Strong performance of reproductive health–focused clinics on key indicators

Because the majority (72%) of Title X clinics in 2015 reported having a reproductive health focus, the patterns found when comparing reproductive health–focused clinics with primary care–focused clinics were very similar to those reported above on key indicators related to facilitating method initiation and continuation. Compared with primary care–focused clinics, those specializing in reproductive health care were significantly more likely to provide initial oral contraceptive supplies and refills on-site (72% vs. 40%), provide initial oral contraceptive pills using the quick-start protocol (88% vs. 66%), allow women to delay their pelvic exam when initiating hormonal contraceptive (89% vs. 76%), provide LARC methods to adolescents or nulliparous women (75–83% vs. 54–56%), and offer same-day insertion of LARC methods (49–57% vs. 32–43%).

Strong performance of Planned Parenthood clinics on key indicators

When comparing the different types of publicly funded family planning clinics on these key indicators, we found wide variation with regard to protocols aimed at facilitating women’s timely access to and continuation of a wide range of contraceptive services and supplies. By far, Planned Parenthood clinics perform better than all other clinic types on nearly all measures. Eighty-three percent provided initial oral contraceptive supplies and refills on-site, as did 76% of health departments, while far smaller proportions of FQHCs and "other" clinics (34–56%) did so. Nearly all (99%) of Planned Parenthoods used the quick-start protocol for oral contraceptives, compared with 65–81% for all other clinic types; 99% offered a delayed pelvic exam, compared with 76–84% for all other clinic types; 95–97% provided LARC methods to adolescents or nulliparous women, compared with 55–76% for all others; and 81–83% offered same-day insertion of LARC methods, compared with 30–54% of all others.

Health departments still struggling

On most key indictors around method provision and facilitation of method initiation and continuation, health department clinics lagged far behind Planned Parenthoods, although they were often similar to FQHCs and "other" clinics. Exceptions to this pattern were health departments’ strong performance on providing oral contraceptive supplies and refills on-site (76%) and their provision of same-day injectable contraceptives (95%). However, access to care at health department clinics for care was reduced relative to other types of clinics because health departments were the least likely provider type to offer same-day appointments, had the longest wait times for an appointment and were the least likely to offer extended hours in the evening or on weekends. Moreover, health departments are struggling to keep up with available revenue sources and modern technology. In 2015, health department clinics were the least likely of all provider types to report having one or more contracts with health plans (73% vs. 81–98%), despite nearly doubling the proportion with contracts in 2010 (36%).3 They were also the least likely to offer any online services for clients: Three percent versus 11–74% had online appointment scheduling, 4% versus 19–32% offered online prescription refills, and 10% versus 22–34% allowed clients to communicate with medical staff online often or sometimes. Finally, nearly half (49%) of health departments reported that some contraceptive methods were not always stocked due to costs.

FQHCs were similar to health departments on key measures of method availability and dispensing, lagging far behind Planned Parenthood clinics, especially on those measures related to LARC availability and dispensing protocols. They also trailed far behind all other clinic types in terms of on-site availability of the most popular reversible method, oral contraceptives. FQHCs did show improvement in some protocols over time—for example, a higher proportion used quick-start protocols or offered delayed pelvic exams in 2015 than in 2010—but there was no change in the proportion offering oral contraceptives on-site. On the other hand, compared with all other clinic types, FQHCs had a larger share of client visits by women covered by Medicaid or other public insurance and they were similar to Planned Parenthoods in terms of having a high proportion of clinics contracting with Medicaid or private health plans.

Improvements and continuing challenges

Publicly funded family planning clinics have faced numerous challenges in recent years, from funding cuts and political threats to administrative changes needed for contracting with health plans. And while there is evidence that the numbers of clients served by the network of clinics have dropped between 2010 and 2015, this report shows that clinics remain a vital source of care and that, despite the challenges they face, many clinics have stepped up to the challenge—improving quality of care and responding to the demands of a changing health care marketplace. Publicly funded clinics have improved on a number of the service delivery hurdles identified in our 2010 report. In addition to increasing the number of contraceptive methods and selection of noncontraceptive services offered, clinics were also more likely to offer same-day appointments and to have a shorter average wait time for appointments in 2015 than they were in 2010. In this period, clinics became increasingly likely to offer oral contraceptives using the quick-start protocol or to offer a delayed pelvic exam, and they were less likely to report not stocking certain methods because of their high cost. Finally, the proportions of clinics that reported contracts with Medicaid health plans doubled between 2010 and 2015 (40% to 80%), and the proportions that reported contracts with private health plans more than doubled (33% to 73%), indicating a rapid ramping up of their ability to function successfully in the new health care marketplace.

Lessons learned

The network of publicly funded family planning clinics is made up of a diverse set of providers functioning under different administrative and regulatory umbrellas. By comparing the services and protocols offered by different types of clinics, we found clear differences in how well clinics are doing to ensure the most accessible and highest quality care for women seeking contraceptive and other sexual and reproductive health care services. Title X–funded clinics, in particular, offered services and protocols that are quite different, and often significantly better, than those offered by clinics that provide contraceptive services but do not rely on Title X funding. The strong performance of Title X sites is likely due both to the added flexibility that Title X funds provide and to Title X program guidelines, which encourage best practices for quality contraceptive care. Policymakers and program planners can learn from these results and design strategies for expanding the experiences of Title X to the broader network of clinics.

FOOTNOTES

*FQHC look-alikes are part of the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration’s Health Center Program and provide health care services to individuals regardless of their ability to pay, but do not receive FQHC program funding.

†Of these, 25 states had implemented a family planning–specific expansion by February 2015 (Alabama, California, Connecticut, Georgia, Iowa, Indiana, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Virginia, Washington and Wisconsin) and 28 states and the District of Columbia had implemented a full-benefit Medicaid expansion under the ACA by February 1, 2015 (Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington and West Virginia).

‡In 2010, there were 13 reversible methods included on the survey and in 2015 there were 14. The methods included differed because some methods that were on the market in 2010 were no longer available in 2015, while others were introduced. The proportion of clinics offering more than 10 methods may reflect these changes in method availability.

§This question was asked differently in 2015 than in 2010, so no trend data are presented.

REFERENCES

1. Frost JJ, Frohwirth L and Zolna MR, Contraceptive Needs and Services, 2014 Update, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2016, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/contraceptive-needs-and-services-2014….

2. Frost JJ, U.S. Women’s Use of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services: Trends, Sources of Care and Factors Associated with Use, 1995–2010, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2013, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/us-womens-use-sexual-and-reproductive….

3. Frost JJ et al., Variation in Service Delivery Practices Among Clinics Providing Publicly Funded Family Planning Services in 2010, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2012, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/variation-service-delivery-practices-….

4. Frost JJ et al., Return on investment: a fuller assessment of the benefits and cost savings of the U.S. publicly funded family planning program, Milbank Quarterly, 2014, 92(4):696–749.

5. Frost JJ, Henshaw SK and Sonfield A, Contraceptive Needs and Services: National and State Data, 2008 Update, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2010.

6. Frost JJ, Zolna MR and Frohwirth L, Contraceptive Needs and Services, 2010, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2013, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/contraceptive-needs-and-services-2010.

7. Frost JJ, Zolna MR and Frohwirth L, Contraceptive Needs and Services, 2012 Update, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2014, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/contraceptive-needs-and-services-2012….

8. Frost JJ, Frohwirth L and Zolna MR, Contraceptive Needs and Services, 2013 Update, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2015, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/contraceptive-needs-and-services-2013….